What if he could actually go to King’s Landing, or The Wall? And what if he took the Kardashians with him?? That’s a little bit what THE MAP OF TIME by Félix J. Palma is like.

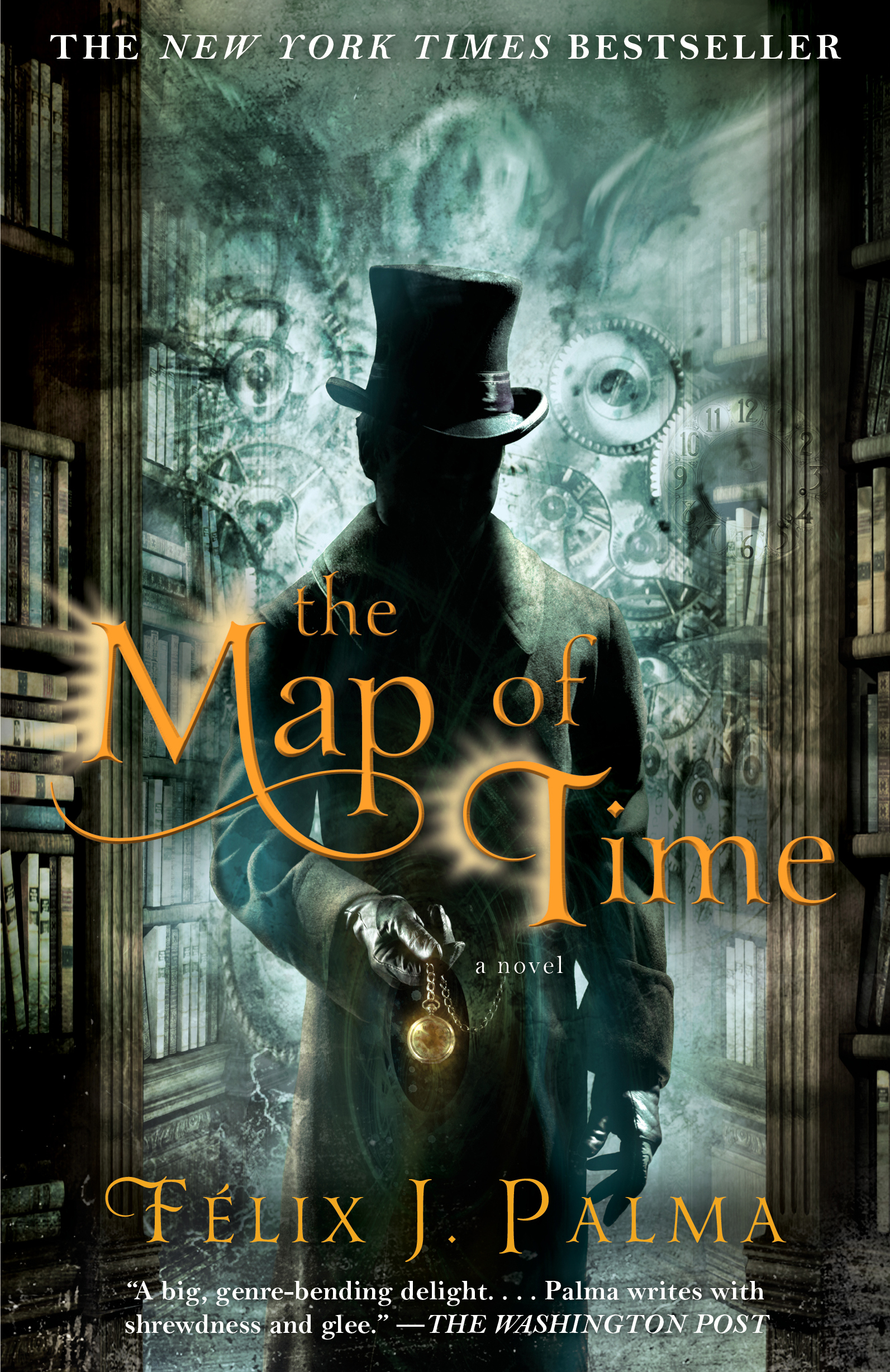

I saw this book floating around my office right after it was published in 2011. I thought, “Ooh. Cool cover.” And the blurb sounded fascinating. I’m pretty sure my thought process was, “H.G. Wells as a character in a steampunk, sci-fi mashup about time-travel? OK, I’m in!” And yeah, I started reading it because I liked the cover. Just because I work in publishing doesn’t mean I’m high-minded, folks. Moving along! —

Our story is really three plotlines woven together in the year 1896:

- Andrew Harrington, a wealthy young Londoner, is bereaved over his murdered lover. His cousin helps him find a way to travel back in time to try and stop her death – but does it really work? Could it ever?

- Claire Haggerty, another wealthy young Londoner, is bored out of her mind with life, until she visits a local business which promises its customers a trip to the year 2000 to watch humans battle robots in a destructive war. She meets the human rebellion’s leader, and she disrupts past, present and future (without the Kardashian tendency to leave blogger fury in her wake).

- H.G. Wells, the godfather of sci-fi, is forced to help Andrew and his cousin with attempting time travel. He wrestles with his own desires to move through parallel universes and whether time and history should be changed for the better.

Throughout all this, we meet Bram Stoker, Jack the Ripper, Henry James, and a host of other turn-of-the-century characters as our heroes move through time, seeking better lives and changing the course of the future.

This is a deep dive into a crazy-cool mashup of steampunk, sci-fi literature. You might remember that mashups had a heyday a few years ago with titles like Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, or THE War of the Worlds, plus Blood, Guts and Zombies. But THE MAP OF TIME isn’t just an exercise in taking classic literature and adding monster movie elements. It employs the engulfing, rich voice of Victorian England description, rumination and detail. Conversation is proper and either taciturn or loquacious. The narrator takes many liberties and cheekily delights in telling you that he won’t describe something because “I see no need to describe it”. It’s quite enjoyable to be reminded by the narrator that he’s doing this because he can, and simply because you’re reading a book after all.