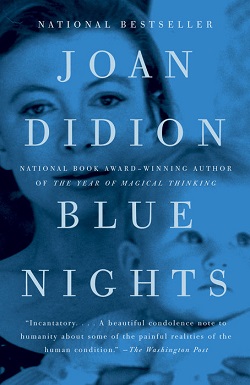

To love and to lose is an experience universal to humankind. None among us will leave this earth having evaded the sorrow of losing someone dear to the ravages of time, or illness, or death. As such, the stories we tell are woven with the fibers of this loss. It would be easy, then, for an author to fall into well-worn metaphors—the heartache, the disbelief, the loved one as an ever present specter preserved in memory. Yet somehow in Blue Nights, Joan Didion addresses all of these themes without pandering to familiar clichés of grief.

Having established herself as a preeminent voice on mourning with The Year of Magical Thinking, a memoir chronicling the sudden loss of her husband, Didion crafts yet another searing portrait of her daughter Quintana Roo’s premature death in Blue Nights. She is unapologetic in dismantling the comfortable platitudes often associated with loss, instead declaring the bitter truth at hand with the incisiveness that has come to characterize her writing. She recalls the reactions of friends and acquaintances following her daughter’s death: “‘You have your wonderful memories,’ people said later, as if memories were solace. Memories are not. Memories are by definition of times past, things gone . . . Memories are what you no longer want to remember.” Didion indicates that sometimes there are moments in the depths of darkness from which no silver lining can be extracted—and that’s okay. For anyone who has experienced loss, this assertion is catharsis and affirmation and enlightenment.

In addition to its freshly articulated ruminations on grief, Blue Nights also addresses the complexities of parenthood. The themes of doubt and fear resonate throughout, beginning at the very moment of Quintana’s adoption: “so [terrible] as to be unthinkable, except I did think it, everyone who has ever waited to bring a baby home thinks it: what if I fail to love this baby?” Didion reveals that this uncertainty is part and parcel of parenthood, as well as of the grief experienced when her role as a mother comes to a sudden end. During Quintana’s childhood and adolescence, she expresses the fear that she has not done her duties as a parent. This is a fear that follows her through Quintana’s illness and death.

As we enter a new year, a book on mourning may not be at the top of one’s reading list. Yet despite the heavy nature of the subject matter, Blue Nights is an enlightening, and I would argue, necessary read. Didion has distinguished herself as a remarkably perceptive writer, one to whom we must pay heed. She imparts extraordinary wisdom quietly, sans showy flourishes and self-congratulation. Rather, the searing truths planted throughout her work are delivered plainly, and her reader is left to digest, recycle, or adopt her wisdom as needed. And in the landscape of literature that deals with loss, where the truth is often obscured by flowery metaphors and fluffy language, this unequivocal wisdom certainly is needed.