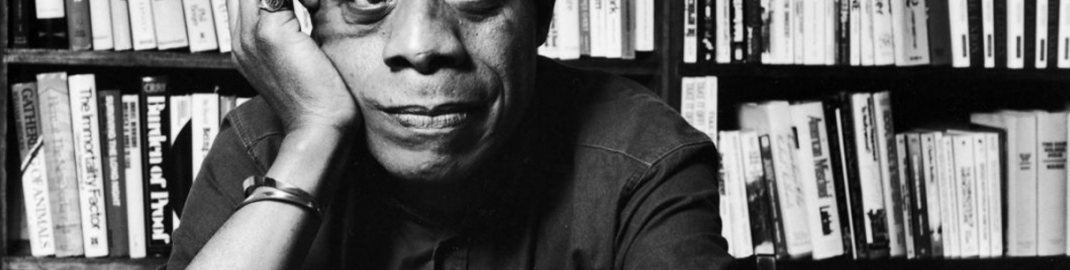

There is something about him. What is it, what is it? Oh, I don’t know. I can’t put it into words. But I’m telling you, there’s something about this man they call James Baldwin, who died before I was born and whose legacy was posted on the walls before I could read. I’m telling you again, and again, I can feel it, I can see it—there’s something about this man. I just know it.

Oh, I know it alright, and you will, too. Just look into those deep-set annular eyes, eyes like a chameleon, eyes that look up and around and through you, eyes that carry sorrow and great tenderness, eyes restless to see something we all see but cannot know. Listen to his voice. A voice that turns words into little drums; a voice comfortable with speed, graceful like a swooping hawk. Look into his boyish face and toothy smile. What is it, what is it?

Read his words. Read his words again, and again, and see what he sees and what we see but cannot know. What is humiliation? What is degradation? Are they parasites, do they feed on certain people, creep and lurk and eat and grow stronger and before you know it they’ve taken over and you, innocent, depleted, are left for dead?

In 1948, James Baldwin left New York and travelled to Paris. He didn’t speak French and arrived with forty dollars to his name. He was twenty-four years old. But being broke or not speaking the native language was of no consequence. In fact, Baldwin was relieved. He needed to leave America. Two years earlier, a close friend of his committed suicide by jumping off the George Washington Bridge. Baldwin was learning what being black in America meant in the middle of the twentieth century. People were being killed, humiliated, and degraded. As Baldwin told Jordan Elgrably in his 1984 Paris Review interview, he knew what it meant to be white and what it meant to be black, and that he knew then that his life could go only one of two ways: either he would be killed or he would kill someone. “Looking for a place to live. Looking for a job. You begin to doubt your judgment, you begin to doubt everything. You become imprecise. And that’s when you’re beginning to go under. You’ve been beaten, and it’s been deliberate. The whole society has decided to make you nothing.” Humiliation has its limits. It pries into you and makes you have doubt. It thaws on your mind and convinces you of its language. It becomes very persuasive. Rather than go mad, the young Baldwin fled. To Paris. But it could have been anywhere. It just couldn’t be in America.

For five years, Baldwin toiled over Go Tell It on the Mountain, which he started when he was seventeen. He wrote upstairs at the Café de Flore and in the Hotel Verneuil, and finally finished the book during a brief trip to Switzerland. He admitted that the novel was very difficult to finish. He started so young, of course, and originally the book was dedicated to exploring the relationship Baldwin shared with his father. But it was equally difficult because in order for the novel to succeed, Baldwin would have to wrestle with himself. And yet nothing was more necessary. If he was to write at all, he needed to finish this book.

In 1953, ten years after Baldwin started it, Go Tell It on the Mountain was published. The novel, now considered one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century, was praised by critics and launched Baldwin’s literary career. Throughout the sixties and seventies, he would become a regular on television. He famously debated the noted conservative William F. Buckley for a national audience. He became, perhaps unwillingly, the critical voice against the treatment of African-Americans, and his shrewd and impassioned arguments forced significant public discourse on the issues of race in America.

But before he became the man we know as James Baldwin, the same man whose writing we read in school, he was wrestling with himself and trying to uncouple the hatred inside of him. He was trying to understand his father and himself. He was thousands of miles from home, in a foreign country, trying desperately to save himself. And the result is Go Tell It on the Mountain. It is a heartbreaking and difficult book. It is an exorcism. Like the great preachers, Baldwin tipples the senses, and drives away the demons. But most importantly, it is an honest book. And maybe that, however incomplete, is what I see. There is something about him. He’s authentic.