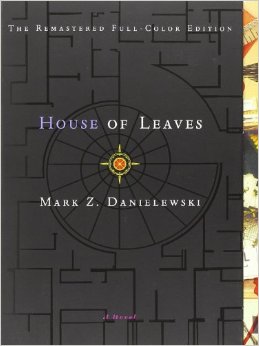

It is too mild to say that I have never read anything like House of Leaves. In fact, I’ve never read anything that even lands in its realm. Long before I finally picked it up myself, I had heard rumblings of its power—it had been deemed the scariest book some had ever read, and also the sexiest. Friends told me that it had altered their lives in ways big and small. Johnny Truant, the novel’s narrator, issues an ominous warning to readers in the introduction: “This much I’m certain of: it doesn’t happen immediately. You’ll finish and that will be that, until a moment will come . . . you’ll suddenly realize things are not how you perceived them to be at all.”

The story centers on photojournalist Will Navidson, who one day makes an alarming discovery: when he measures the dimensions of his house from the inside, they are not the same as when measured from the outside. Soon after, the house begins to reveal other inconsistencies. Will and his wife Karen discover a door—a door that should logically open to their backyard, but in fact opens to a massive and ever expanding network of hallways, rooms, and an immense spiral staircase. Will cannot resist the impulse to explore the expanse, and soon embarks on a series of expeditions into the inhospitable space with a team of friends and explorers.

Postmodernism is characterized by a rejection of form, and House of Leaves does nothing if not embrace its own unconventionality. Navidson’s exploration of the house is documented in a film-within-the-text called The Navidson Record, about which an old man named Zampano has purportedly written this book. The troubled young man who discovered Zampano’s manuscript, Johnny Truant, adds his own rambling footnotes to the text. And then there are the nameless, seemingly all-knowing Editors, who insert yet another layer of footnotes into Truant’s and Zampano’s narration.

If the multiple layers of storytelling aren’t enough to leave you both highly engrossed and a bit discombobulated, perhaps the dynamic nature of the physical text itself will do the trick. In a chapter that dives deep into the mythology of labyrinths, the text becomes increasingly meandering—inscrutable footnotes and crossed out sentences abound. Later, during a particularly treacherous exploration of the house, a single word occupies each page—forcing the reader to flip frantically through the pages, mirroring the adrenaline pumping, heart racing action contained therein.

Everything about this book defies distillation, from the meta-narrative structure to the footnotes within footnotes to the layered and complex plot. The only way to truly appreciate Danielewski’s masterpiece is to pick it up and let it engulf you. It has a life of its own, and it will change yours.