My love of poetry is what led me to truly appreciate first the memoir, and then the novel. It’s not that I hadn’t read or enjoyed memoirs and novels before, but that learning to savor the careful language choice, sound, and both experimental and traditional structures of poems taught me to find sonic, visual, and intellectual beauty in other forms of writing. Now it’s no surprise that some of my favorite works of both fiction and nonfiction are written by poets themselves! In honor of National Poetry Month this April, here are some of my favorite poets’ novels and memoirs that tell compelling, empathetic, and valuable tales with the most irresistible, lush language.

9 Beautifully Written Books by Poets

In musical prose and romantic sentences, LEONORA IN THE MORNING LIGHT tells a fictionalized version of the affair between surrealist artists Leonora Carrington and Max Ernst during World War II. Although told by a bright and compassionate third-person narrator, this novel switches between the points of view of Max and Leonora across a span of a few years. Even those who don’t typically read historical fiction will appreciate this writing, which exudes sensuality and passion.

*One of Oprah Daily’s Most Anticipated Historical Fiction Novels That Will Sweep You Away*

“Michaela Carter’s training as a poet and painter shines through from the first page of this vivid, gorgeous novel based on the lives of Leonora Carrington and Max Ernst. Told with all the wild magic and mystery of the Surrealists themselves, Leonora in the Morning Light fearlessly illuminates the life and work of a formidable female artist.” —Whitney Scharer, bestselling author of The Age of Light

For fans of Amy Bloom’s White Houses and Colm Tóibín’s The Master, a “gorgeously written, meticulously researched” (Jillian Cantor, bestselling author of Half Life) novel about Surrealist artist Leonora Carrington and the art, drama, and romance that defined her coming-of-age during World War II.

1940. A train carrying exiled German prisoners from a labor camp arrives in southern France. Within moments, word spreads that Nazi capture is imminent, and the men flee for the woods, desperate to disappear across the Spanish border. One stays behind, determined to ride the train until he reaches home, to find a woman he refers to simply as “her.”

1937. Leonora Carrington is a twenty-year-old British socialite and painter when she meets Max Ernst, an older, married artist whose work has captivated Europe. She follows him to Paris, into the vibrant world of studios and cafes where rising visionaries of the Surrealist movement like Andre Breton, Pablo Picasso, Lee Miller, Man Ray, and Salvador Dali are challenging conventional approaches to art and life. Inspired by their freedom, Leonora begins to experiment with her own work, translating vivid stories of her youth onto canvas and gaining recognition under her own name. It is a bright and glorious age of enlightenment—until war looms over Europe and headlines emerge denouncing Max and his circle as “degenerates,” leading to his arrest and imprisonment. Left along as occupation spreads throughout the countryside, Leonora battles terrifying circumstances to survive, reawakening past demons that threaten to consume her.

As Leonora and Max embark on remarkable journeys together and apart, the full story of their tumultuous and passionate love affair unfolds, spanning time and borders as they seek to reunite and reclaim their creative power in a world shattered by war. When their paths cross with Peggy Guggenheim, an art collector and socialite working to help artists escape to America, nothing will be the same.

Based on true events and historical figures, Leonora in the Morning Light is “a deeply involving historical tale of tragic lost love, determined survival, the sanctuary of art, and the evolution of a muse into an artist of powerfully provocative feminist expression” (Booklist, starred review).

Maggie Smith is one of the most popular poets writing today, and readers of poetry and creative nonfiction alike will flock to this shimmering, lyrical memoir that takes its name from the final line in Smith’s viral poem “Good Bones” (from the book of the same title). Brilliant not just for what it tells but also what it omits, YOU COULD MAKE THIS PLACE BEAUTIFUL is written in short chapters and vignettes, with a poem or an epigraph tucked in here and there. In brief but potent passages, Smith pieces together the story of her marriage—how it came to be, how it fell apart—and her decision to champion hope in the face of heartbreak. This compelling, conversational memoir is as much about Smith’s hurt and anger as it is about her journey, in which she learns to not give in to anger but rather to lean in to healing and hope.

“[Smith]...reminds you that you can...survive deep loss, sink into life’s deep beauty, and constantly, constantly make yourself new.” —Glennon Doyle, #1 New York Times bestselling author

The bestselling poet and author of the “powerful” (People) and “luminous” (Newsweek) Keep Moving offers a lush and heartrending memoir exploring coming of age in your middle age.

“Life, like a poem, is a series of choices.”

In her memoir You Could Make This Place Beautiful, poet Maggie Smith explores the disintegration of her marriage and her renewed commitment to herself in lyrical vignettes that shine, hard and clear as jewels. The book begins with one woman’s personal, particular heartbreak, but its circles widen into a reckoning with contemporary womanhood, traditional gender roles, and the power dynamics that persist even in many progressive homes. With the spirit of self-inquiry and empathy she’s known for, Smith interweaves snapshots of a life with meditations on secrets, anger, forgiveness, and narrative itself. The power of these pieces is cumulative: page after page, they build into a larger interrogation of family, work, and patriarchy.

You Could Make This Place Beautiful, like the work of Deborah Levy, Rachel Cusk, and Gina Frangello, is an unflinching look at what it means to live and write our own lives. It is a story about a mother’s fierce and constant love for her children, and a woman’s love and regard for herself. Above all, this memoir is an argument for possibility. With a poet’s attention to language and an innovative approach to the genre, Smith reveals how, in the aftermath of loss, we can discover our power and make something new. Something beautiful.

Written during the height of Covid-19, poet Clare Pollard’s debut novel is narrated by an unnamed writer, a professor of classics who is researching the Oracle of Delphi and navigating quarantine in the UK with her husband and son. Each chapter of this witty novel is named for a different method of predicting the future (osteomancy, rhapsodomancy, auramancy, to name a few). After introducing the story of the Oracle of Delphi, the narrator alternates between describing her research findings and sharing the comical, desperate ways she and her family are responding to the pandemic. Many readers will relate to the narrator’s experience of the Covid years, of marital troubles, motherhood, and the desire to find meaning and hope in the age of Trump.

For readers of Jenny Offill, Deborah Levy, and Olivia Laing, an exquisite debut novel about a classics academic researching prophecy in the ancient world, just as the pandemic descends and all visions of her own family’s future begin to blur.

Covid-19 has arrived in London, and the entire world quickly succumbs to the surreal, chaotic mundanity of screens, isolation, and the disasters small and large that have plagued recent history. As our unnamed narrator—a classics academic immersed in her studies of ancient prophecies—navigates the tightening grip of lockdown, a marriage in crisis, and a ten-year-old son who seems increasingly unreachable, she becomes obsessed with predicting the future. Shifting her focus from chiromancy (prophecy by palm reading) to zoomancy (prophecy by animal behavior) to oenomancy (prophecy by wine), she fails to notice the future creeping into the heart of her very own home, and when she finally does, the threat has already breached the gates.

Brainy and ominous, funny and sharp, Delphi is a snapshot and a time capsule—it both demythologizes our current moment and places our reality in the context of myth. Clare Pollard has delivered one of our first great novels of this terrible moment, a mesmerizing story of our pasts, our presents, and our futures, and how we keep on living in a world that is ever-more uncertain and absurd.

What ensues when a poet rescues a baby magpie in the Welsh countryside? A love story full of feathers, laughter, tears, and an examination of the gifts of human-animal relationships. Written in the form of a diary with dated entries, GEORGE documents the life of the titular character, a baby magpie the author rescues on her remote property after a storm. Frieda Hughes, the daughter of poets Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes, adds George to her menagerie (which includes a variety of dogs and owls) and finds comfort in their special bond while her marriage crumbles apart. This funny, utterly charming memoir will make you laugh and cry. It is full of exquisite nature imagery, and you won’t be able to walk away without completely falling for the stubborn, vibrant-feathered George.

“He was a hectic, unprincipled bird, but it was impossible not to love him.” From poet and painter Frieda Hughes, a memoir of love, obsession, and feathers.

When Frieda Hughes moved to the depths of the Welsh countryside, she was expecting to take on a few projects: planting a garden, painting, writing her poetry column for The Times (London), and possibly even breathing new life into her ailing marriage. But instead, she found herself rescuing a baby magpie, the sole survivor of a nest destroyed in a storm—and embarking on an obsession that would change the course of her life.

As the magpie, George, grows from a shrieking scrap of feathers and bones into an intelligent, unruly companion, Frieda finds herself captivated—and apprehensive of what will happen when the time comes to finally set him free.

With irresistible humor and heart, Frieda invites us along on her unlikely journey toward joy and connection in the wake of sadness and loss; a journey that began with saving a tiny wild creature and ended with her being saved in return.

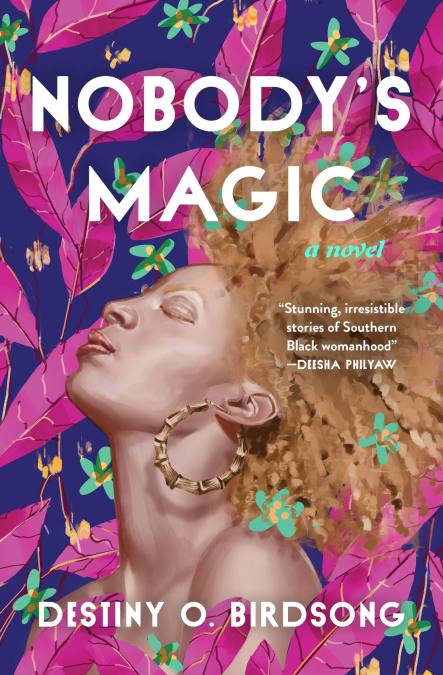

This triptych novel follows three women—Suzette, Maple, and Agnes—on their journeys of self-discovery as three Black women living with albinism in Shreveport, Louisiana. Suzette has been sheltered her whole life, ever since a friend’s grandmother threatened to gouge out her eyes, but now she is finally ready to go to school for something she loves (fashion), explore her sexuality, and live life to the fullest, despite her parents’ desire to hide her away. Maple loses her mother, who is also her best friend, in a drive-by shooting, and then attempts to process her grief, falling in love with a man who actually knows how she feels. Agnes tries to find meaning in a dull job when she falls in love with a security guard and embarks on a dangerous adventure with him. Birdsong, herself a Black woman with albinism who hails from Shreveport, writes a thrilling novel that completely transported me, and these three beautiful women endeared themselves to me. The plot is gripping, the characters complex and well-rounded, and the exploration of the struggles faced by (and power found within) Black women is executed with great artistic precision.

In this moving, heartbreaking exploration of the author’s childhood—in which he was kidnapped from his Black father by his white maternal grandparents—McCrae asks questions and explores the fluidity of memory in an attempt to come to terms with a past scarred by racism and hate. McCrae’s quest mirrors our nation’s struggle to acknowledge and heal from a convoluted past filled with racial inequity and violence. The rhetorical questions and long, intentionally wandering sentences read like tunnels, or pathways on a map, the author and reader alike trying to find a way home to the truth, to understanding. This is a truly worthy adventure to take, a book that is rich with metaphor and compassion and an honest desire to know the truth. Anyone looking for a vulnerable, lyrical meditation on the personal impacts of racism in America will treasure this book.

An unforgettable memoir by an award-winning poet about being kidnapped from his Black father and raised by his white supremacist grandparents.

When Shane McCrae was three years old, his grandparents kidnapped him and took him to suburban Texas. His mom was white and his dad was Black, and to hide his Blackness from him, his maternal grandparents stole him from his father. In the years that followed, they manipulated and controlled him, refusing to acknowledge his heritage—all the while believing they were doing what was best for him.

For their own safety and to ensure the kidnapping remained a success, Shane’s grandparents had to make sure that he never knew the full story, so he was raised to participate in his own disappearance. But despite elaborate fabrications and unreliable memories, Shane begins to reconstruct his own story and to forge his own identity. Gradually, the truth unveils itself, and with the truth, comes a path to reuniting with his father and finding his own place in the world.

A revelatory account of a singularly American childhood that hauntingly echoes the larger story of race in our country, Pulling the Chariot of the Sun is written with the virtuosity and heart of one of the finest poets writing today. And it is also a powerful reflection on what is broken in America—but also what might heal and make it whole again.

His entire life, Owen Tanner has been living in a bubble: his mother has kept him hidden away since she discovered, when he was a baby, that he has a bird living in a hole in his chest. Owen’s mother can only imagine the worst would happen if doctors, also known as the Army of Acronyms, were to discover the bird. As a teenager, Owen and his spirited bird, Gail, grow tired of their life of hiding and yearn for freedom, whatever the consequences may be. This work of magical realism serves as an allegory for the dangers of forcing someone to live a closeted life and not accepting them for who they really are. This is a particularly pertinent read for today.

Longlisted for The Center for Fiction 2022 First Novel Prize

A “poignantly rendered and illuminating” (The Washington Post) coming-of-age story about “the ways in which family, grief, love, queerness, and vulnerability all intersect” (Kristen Arnett, New York Times bestselling author). Perfect for fans of The Perks of Being a Wallflower and The Thirty Names of Night.

Though Owen Tanner has never met anyone else who has a chatty bird in their chest, medical forums would call him a Terror. From the moment Gail emerged between Owen’s ribs, his mother knew that she had to hide him away from the world. After a decade spent in isolation, Owen takes a brazen trip outdoors and his life is upended forever.

Suddenly, he is forced to flee the home that had once felt so confining and hide in plain sight with his uncle and cousin in Washington. There, he feels the joy of finding a family among friends; of sharing the bird in his chest and being embraced fully; of falling in love and feeling the devastating heartbreak of rejection before finding a spark of happiness in the most unexpected place; of living his truth regardless of how hard the thieves of joy may try to tear him down. But the threat of the Army of Acronyms is a constant, looming presence, making Owen wonder if he’ll ever find a way out of the cycle of fear.

“An honest celebration of life and everything we need right now in a book” (Andrew Sean Greer, Pulitzer Prize–winning author), The Boy with a Bird in His Chest grapples with the fear, depression, and feelings of isolation that come with believing that we will never be loved for who we truly are and learning to live fully and openly regardless.

MENTIONED IN:

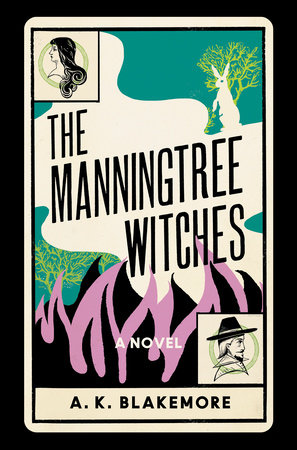

It’s the 17th century in England, and Calvinism and Puritanism are running amok, threatening the existence of an all-women community in Manningtree. Suddenly men come to Manningtree and question these women’s lives and intentions—men such as the Witchfinder General, dressed all in black. Narrated by Rebecca West, the only literate woman in her community, this witch-hunt tale feels startingly familiar as it depicts a society in which suspicion and oppression run rampant and women find themselves subject to the whims of powerful white men. Blakemore’s debut novel bursts with all-around vigorous prose and visceral descriptions of the female body. Blakemore’s sophomore novel, GLUTTON, which publishes in October, promises to be another unputdownable lyrical stunner!

This devastating story set in rural Canada during World War II follows Rose Marie—a young Blackfoot girl who is ripped from her native home and placed in St. Mark’s, a Catholic boarding school—and Mother Grace, the stern head nun. Rose Marie doesn’t quite fit in at St. Mark’s, where rules abound and few girls leave alive. When she visits Black Apple, the nearby town, Rose Marie realizes that she doesn’t exactly fit in there, either, and she has to reconsider who she really is. Joan Crate doesn’t hold her punches when describing the heartbreaking circumstances that many Native children faced in Canada in the early 20th century, which makes this novel all the more triumphant. BLACK APPLE is a challenging but important book that resounds with echoes of the past.

A dramatic and lyrical coming-of-age novel about a young Blackfoot girl who grows up in the residential school system on the Canadian prairies.

Torn from her home and delivered to St. Mark’s Residential School for Girls by government decree, young Rose Marie finds herself in an alien universe where nothing of her previous life is tolerated, not even her Blackfoot name. For she has entered into the world of the Sisters of Brotherly Love, an order of nuns dedicated to saving the Indigenous children from damnation. Life under the sharp eye of Mother Grace, the Mother General, becomes an endless series of torments, from daily recitations and obligations to chronic sickness and inedible food. And then there are the beatings. All the feisty Rose Marie wants to do is escape from St. Mark’s. How her imagination soars as she dreams about her lost family on the Reserve, finding in her visions a healing spirit that touches her heart. But all too soon she starts to see other shapes in her dreams as well, shapes that warn her of unspoken dangers and mysteries that threaten to engulf her. And she has seen the rows of plain wooden crosses behind the school, reminding her that many students have never left here alive.

Set during the Second World War and the 1950s, Black Apple is an unforgettable, vividly rendered novel about two very different women whose worlds collide: an irrepressible young Blackfoot girl whose spirit cannot be destroyed, and an aging yet powerful nun who increasingly doubts the value of her life. It captures brilliantly the strange mix of cruelty and compassion in the residential schools, where young children are forbidden to speak their own languages and given Christian names. As Rose Marie matures, she finds increasingly that she knows only the life of the nuns, with its piety, hard work and self-denial. Why is it, then, that she is haunted by secret visions—of past crimes in the school that terrify her, of her dead mother, of the Indigenous life on the plains that has long vanished? Even the kind-hearted Sister Cilla is unable to calm her fears. And then, there is a miracle, or so Mother Grace says. Now Rose is thrust back into the outside world with only her wits to save her.

With a poet’s eye, Joan Crate creates brilliantly the many shadings of this heartbreaking novel, rendering perfectly the inner voices of Rose Marie and Mother Grace, and exploring the larger themes of belief and belonging, of faith and forgiveness.

MENTIONED IN:

Photo credit: iStock / NataGolubnycha