Signe Pike is the author of the historical series The Lost Queen, which has recently been optioned for television. The second book in the series, The Forgotten Kingdom, is on sale now. Visit her website at www.signepike.com.

Books carry secrets.

As a little girl I suspected this was true, but it wasn’t until I was older that I would discover a secret hidden in a book that would change my life forever.

I’d been studying Celtic history for three years by the time I wandered into a tiny bookshop at the bottom of High Street in Glastonbury, England. It was summer, and I was looking for a break from the heat. There among the shelves I discovered a nonfiction book titled Finding Merlin. Within its pages, I read about Languoreth, a real queen of sixth-century Scotland who had been all but lost beneath the weight of passing centuries.

Languoreth was one of the most powerful queens of early medieval Scotland. Her husband, Rhydderch, ruled the kingdom of Strathclyde from approximately AD 580–AD 614. Scholars know the military campaigns Rhydderch was engaged in, as well as the names of the children descended from their union, whose identities surface in the Welsh Triads, saints’ lives, and king lists. But what I found most intriguing, perhaps, was the fact that this sixth-century queen had a twin brother who amassed a great deal of fame of his own. He was a politician, a warrior, and a pre-Christian man who’d made powerful enemies in his lifetime, enemies who sought to erase his name from public record. His name was Lailoken. But you may better know him as the man who was called Merlin.

Many of us grew up on tales of the wizard Merlin, the gnarled, white-haired mage who stood beside King Arthur of legend. But few are aware that the character of Merlin was likely based on the figure of Lailoken, and the key to proving his existence lies in the historical life of his sister. Captivated by a curiosity I did not yet understand, I began digging through historical sources, searching for every trace of Languoreth I could find. She was named as the wife of Rhydderch in the twelfth-century Life of St. Kentigern by the monk Jocelin of Furness. Her memory was preserved in the fourteenth-century Red Book of Hergest, in a poem titled “The Dialogue Between Myrddin and His Sister Gwenddydd.” She was remembered as Rhydderch’s adulterous queen in a piece of Glasgow folklore called “The Fish and the Ring.” And the Aberdeen Breviary, a sixteenth-century manuscript, did not name Rhydderch’s wife, but referred to her as “the Queen of Cadzow,” a title attached to Languoreth in other sources. These mentions amount to more medieval “press” than can be claimed by any one of Languoreth’s female contemporaries. And as I learned about the heart-wrenching events that took place during her lifetime—including the Battle of Arderydd, one of the most tragic battles of Scottish history that no one remembers—I thought it a travesty that Languoreth had been written out of history, her powerful story never told.

The Arthurian legend has been worked over by countless hands, from medieval monks and imprisoned fifteenth-century knights to nineteenth-century antiquarians and modern-day authors like T. H. White and Marion Zimmer Bradley. Each added their own twist to the tale, resulting in layer upon layer of nonsensical sediment, effectively burying a man of flesh and blood and resurrecting him as a wizened old wizard who shot magic from his fingertips while his illustrious sister was written out of history altogether. How could it be that the existence of such an influential family was wiped so effectively from the collective minds of their own people?

The answer to this question lay in the nature of the enemies Languoreth and her brother, Lailoken, made in their lifetime—men of a new patriarchal religion that sought to subvert the matriarchal influence that had held sway in the British Isles for well over a millennia. Sources make it clear that Languoreth and her brother were bastions of an “Old Way,” one that stood in the path of new power sought by men of the church. The very plausible saga of their lives has been traced now in multiple credible nonfiction books, yet still the discovery of these historical figures who inspired 1,500 years of legend had failed to catch light in the modern mind. Not only that, but even the legendary Arthur can be traced to early medieval Scotland, not Wales or southern England, in the form of a historical warlord named Artúr mac Áedán, who fought and defeated Angle interlopers from across the broad sea.

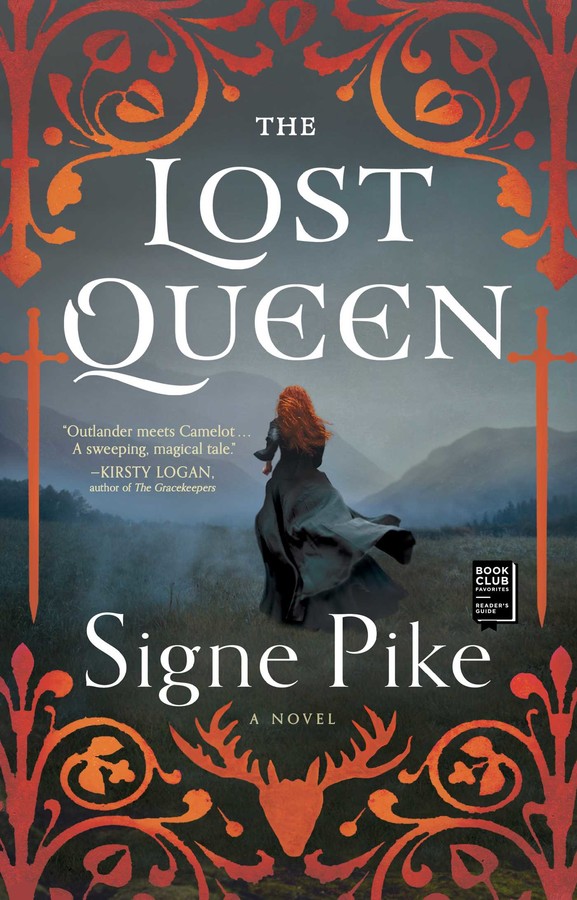

And so it was that the secret buried in a book set me on a new path of my own. Determined to resurrect the lives of the real flesh-and-blood people at the heart of the Arthurian legend, I published the historical novel The Lost Queen in 2018, after six years of writing and research.

When we study the scraps of evidence left behind, one thing becomes apparent: Languoreth and her brother were two individuals who fought to preserve the ancient beliefs of their people in a time of tremendous religious and political upheaval. In days such as these, when so many are in search of moral and political inspiration, theirs is a story that offers both strength and healing. Not because they were magical. But because they were human.

Legends are stories that make no promises of truth. Yet through the study of folklore, history, archaeology, and anthropology, I’ve come to believe that within every legend lies a kernel of truth. We may never be able to prove that the sixth-century man known as Lailoken was the inspiration for the character of Merlin. But Languoreth is a historical figure whose acknowledgment is long overdue. And I have never been all that good at keeping secrets.

Who was the man named Lailoken? And what of our lost queen, Languoreth?

The times this brother and sister lived through, the battles they fought, and the beliefs they fought for may be obscured by slander and veiled by the fog of history. But their enchantment was the real, everyday sort, and it is still accessible to any who seek it.