Each time I sat down to read Anthony Doerr’s recent National Book Award nominee, All the Light We Cannot See, I found myself cocooned in his velvety evocations of Saint-Malo, an enchanting French city perched upon the sea. His narration was captivating and his characters multidimensional, but I was most compelled by the distinct sense of place. I could feel the German gunfire rattling the protagonist’s ancient house and smell the salt of the ocean waves wafting from the shore. This experience could hardly be classified as reading—devouring is perhaps a closer approximation.

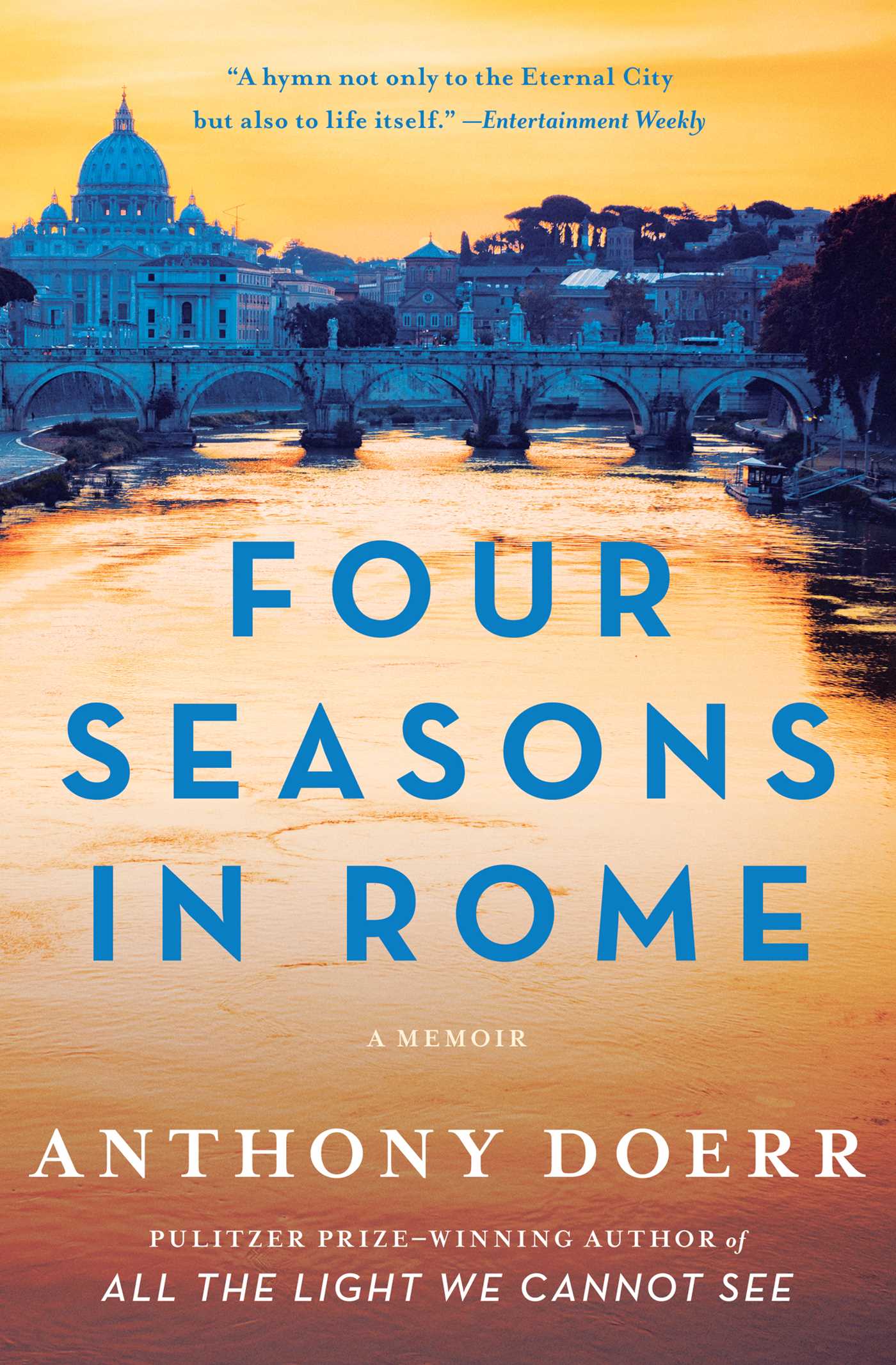

Seeking out more of Doerr’s talent for awakening the senses, I picked up Four Seasons in Rome next. This memoir details the year he spent as a writing fellow in Italy, living with his wife and their twin infant sons. It was during this time that he developed the bare bones of what would, several years later, take shape as All the Light. Here I found the same mouthwatering depictions of a European city seeping with history, with Italian piazzas taking the place of French castles and uneven cobblestoned streets in lieu of attics perched above the sea.

In Four Seasons, I was struck by Doerr’s tender articulation of the difficulties of settling into a life thousands of miles from home. Rather than being transported to an imagined place, I found myself absorbed in my own memories. I had recently spent my own four seasons abroad in Paris, and in every one of Doerr’s cultural gaffes or linguistic mix-ups, I saw a glimmer of my own gauche missteps.

Most Americans harbor some kind of romanticized image of what it must mean to be an expat abroad, and I can’t deny that there is truth in these fantasies. My weeks involved bulk consumption of freshly baked baguettes from my neighborhood boulangerie, which just so happened to boast the best bread in the entire city. This, by the way, was not conjecture but in fact a hard won title: Parisians deem the annual crowning of their city’s champion bread maker a worthy investment of their tax dollars. And yes, wine was cheaper than water, I could wander through dozens of gorgeous museums free of charge, and I routinely had the actual breath taken out of me by the beauty of the city.

Yet the year was undeniably difficult, in unanticipated ways. For Doerr, many of the challenges he faced in Rome emerged from efforts to protect and provide for his sons. While I held no such responsibility, the difficulties of my daily life revolved around the same barriers of culture, bureaucracy, and simply feeling a million miles removed from the familiar.

Mastering a foreign language is certainly the greatest and most universal challenge to daily life abroad. Every interaction, when communicating in a language that is not your mother tongue, presents the opportunity for epic defeat at the hands of a single mispronounced syllable. Doerr recalls his determination one day to purchase tomato sauce, insisting that the grocer hand him the “sugo di pompelmo con basilico.” It is only on his walk home that he realizes he had been adamantly demanding grapefruit sauce with basil.

With this simple anecdote, Doerr captures the essence of the expatriate life, which can be boiled down to a string of grapefruit-sauce days—bitter and cumbersome and delectable.