I remember when the planes hit the twin towers. I was twelve years old. That morning, I refused to wake up. I wanted to sleep in, like every day, with the hope of missing school. That day, like most days, my plan was ruined by an insistent and stern mother.

My friend, Jeff, was anxious to show me the baseball cards he had purchased the previous evening. The day was smoggy and it felt like it would rain. We rose to say the pledge of allegiance and while we held our hands against our hearts, we heard shouting in the hallways. The teacher’s phone rang. The superintendent was charging up and down the hallway. Her voice was shrill and undisciplined; it was the sound of nervousness, possibly fear.

The teacher turned on the television. I didn’t know much about the twin towers. I didn’t know anything about terrorism. All I noticed was the smoke that rose steadily from the side of the building where the sun had rested its gaze. I remember my teacher’s face, drained of emotion, pallid and sweaty, and those of my peers, all of whom looked on silently, some with morbid fascination and others with looks of disbelief. Then the second plane hit, swooping in like a gull in search of food. There was news of a third plane that successfully crashed into the white house. The president, we overheard, was in critical condition. There was news also of the pentagon being attacked. This, too, was successful.

The rest of the day was a blur; I remember my parents picking me up midday and people crying in the streets. It was the day we all knew would change our lives. It was the day America changed, too.

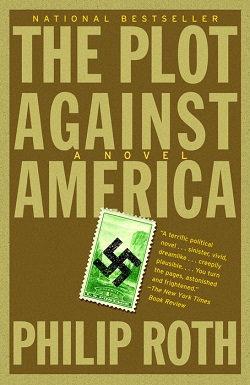

Of course, this version is only partially true. The White House wasn’t attacked and the President wasn’t on Capitol Hill. But this slight modification, changing a haunting event into something even more frightening, is where Philip Roth in Plot Against America succeeds like I’ve never read before. For in 1940, incumbent president Franklin D. Roosevelt loses to the Republican nominee, Charles A. Lindbergh, known, historically, not as a politician but as a famous pilot and Nazi sympathizer. In a classic move of American politicking, Lindbergh convinces the American public of Roosevelt’s bellicose attitude towards the war, his eagerness to intervene, and sermonizes on the benefits of remaining neutral and non-confrontational. History is re-written and America allies with the Third Reich. President Lindbergh finds the ideas of Adolf Hitler convincing and succinct. For a working-class Jewish family who calls America home, this turn of fate is devastating. The American pogrom becomes real.

The book is sinuous and layered; a nightmare spun through the tenacious dimensions of feeling and experience. It is fiction at its best. It’s no surprise that critics have lauded Philip Roth as not only one of the best writers of his generation but among those writing today.