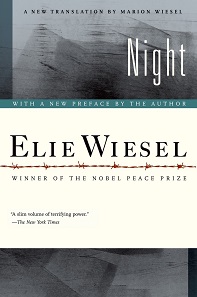

I’ve wanted to read Night by Elie Wiesel for many years. This slim memoir has a legacy all its own, which very few books, either fiction or nonfiction, can claim to have. I don’t know why I’ve avoided it for so long. Perhaps the ubiquity of its influence over the years told me I always had time to visit it when I wanted to, as I remind myself with Proust or James Baldwin or Simone de Beauvoir. That it wasn’t going anywhere. Then, several months ago, while flying to California from New York, I purchased it on my way to the airport. It’s short, hardly a hundred pages, and I finished it just as I was landing in Los Angeles.

Elie Wiesel was only sixteen years old when his family was forced into one of the two ghettos of Sighet, a Romanian town in the Carpathian Mountains, which had, by 1940, come under Hungarian control. That same year, Hungarian authorities allowed the Germans to deport Jews settled in these ghettos to various concentration camps that began sprouting up in German-controlled areas. The Wiesels were taken to Auschwitz-Birkenau, a camp located in contemporary Poland.

I remember walking through the terminal at LAX as the sun’s rays came through the paneled windows of the terminal, their brightness and hue redolent of spring, thinking of nothing but the pure experience of what I had just read, thinking inwardly and paying no mind to the things around me. There was something silly about the people roaming about, the kiosks with candy and magazines, the dull airport music. As if everything had lost its flavor, its sense of life. I waited patiently for a taxi but gave it no thought—I was empty, emotionally stricken, cold and without feeling.

For ten years, Elie Wiesel refused to write down anything about his time spent in those camps. He couldn’t find the appropriate words, if such a thing exists. Are there words, really? We read and write to escape the circumstances of our lives we find undesirable. In some cases, we write to be critical. To be clear. But to relive an experience of unfathomable pain is an altogether different matter. “It wasn’t voluntary. None of us wanted to write. Therefore when you read a book on the Holocaust, written by a survivor, you always feel this ambivalence. On the one hand, he feels he must. On the other hand, he feels . . . if only I didn’t have to,” Wiesel told John S. Friedman of the Paris Review.

What is so immediate about Night is that it offers no diagnostic of the war—it is not a critique of human nature; it is pure record. The sheer experience of living in a nightmare where there are no ends, no exits, and no means of perspective: the immediacy of being reduced to numbers and limbs, being a puppet to the will of the exterminator. Wiesel records in spare, barren prose circumstances that require no embellishment. A pure, unadorned story of human irrationality—realized through the systematic genocide of a people.

Night is a confession told in an unusual style. It doesn’t have an interior element, which isn’t to say the narrator is removed from the horrors that surround him. More so, the events that befall young Wiesel, his father, and the other Jews are so beyond reason, the devaluation of life to dirt, that the absence of reflection produces a harrowing effect. Through this art we are audience to an unraveling nightmare protected by narrative shellac that brings to relief those hours and days and years of insanity. Who can recognize their humanity in such moments? It seems to be a fiction incommensurate with our experience, a howl that fades into the light of dawn before anyone wakes up.

To witness a young son avoid his sick father in order to ensure their rations survive until tomorrow, an old man beaten to a pulp for nothing, artists and musicians singing songs of sorrow while their stomachs grumble from days of hunger, and children crying hopelessly in the arms of resigned mothers; these are not memories one can wash away. These are things beyond words. These are stains, open wounds, manias. Only Elie Wiesel saves us from the vertigo of madness; his humanity saves us from this irreconcilable darkness.