When David Carr collapsed and died in February back at work at The New York Times after an evening public speaking event, calls and texts spread quickly among his multitude of friends hoping to break the news before it began bubbling up, alarming and poorly sourced, on Twitter. I first heard from a friend at the Times, and then I immediately called a close friend of David’s who was not so lucky; he’d just been scanning his feed.

There was a bit of rough poetry in that. Carr, through his Media Equation column and his oversized Twitter footprint (his account still has nearly 500,000 followers), helped popularize and legitimize Twitter. “The real value of the service,” he wrote back in 2010, in Twitter’s infancy, “is listening to a wired collective voice.” He loved how the social media hive sifted through hype to offer up the fascinating and the important—precisely what many of us valued so much in his own work. Now, that hive buzzed about his death at the age of just fifty-eight.

A familiar, colorful portrait emerged of Carr in the coverage that followed: outsized personality with a distinct voice and a Gump-like ability to be where the action is, who overcame an early, crippling addiction to triumph as a top columnist at The New York Times. His media beat contemporary, Jack Shafer, called him “an original persona that was one part shambling hipster, one part Tom Waits, a pinch of Jimmy Breslin, and a dollop of the Mad Hatter.” His writing was “a marvel of wry Midwestern plainness, sprinkled with phrases his colleagues will only ever think of as Carrisms,” the Times’s A. O. Scott wrote. “Something essential was ‘baked in.’ Someone was always competing to be the tallest leprechaun.” He was the runaway star of Page One, the popular documentary about The New York Times; he reportedly introduced his friend Lena Dunham to Judd Apatow, making Girls possible; he became—with a voice so raspy it could cut cable—an improbable familiar TV presence.

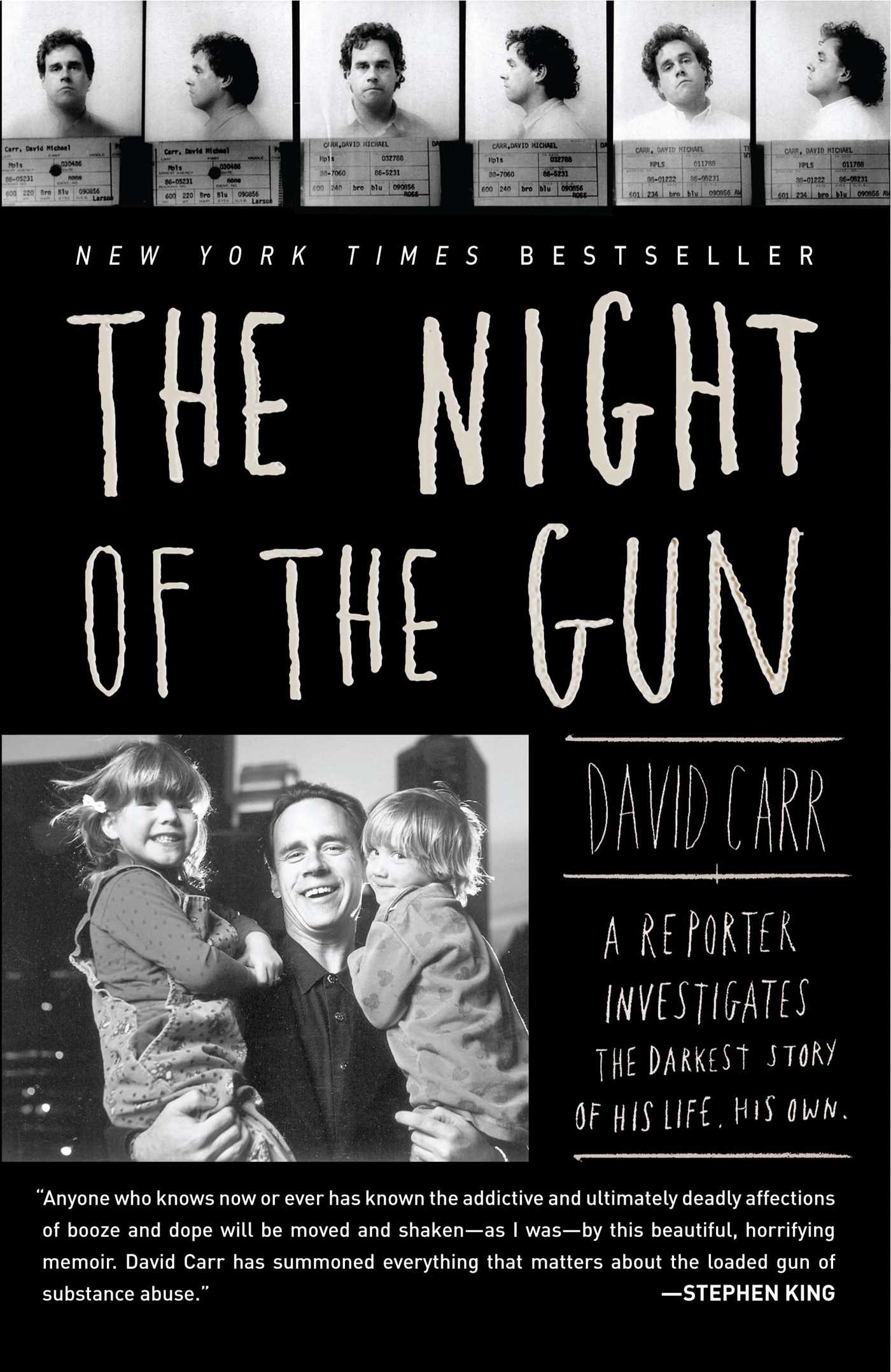

I wondered what David would think about all these tearful and reverent assessments, and a line from his masterwork of self-investigation, The Night of the Gun, echoed: “We all remember the parts of the past that allow us to meet the future.” The Night of the Gun is a memoir that he took no liberties with, thoroughly reporting and researching his own violent drug-dealing, crack-using past. He wasn’t always the shrewd, trusted voice we relied on, and he was the first to tell you about it. And tell us he did.

The brutal honesty of The Night of the Gun makes it not only a gripping read but also the ultimate unsparing biography. “Truly ennobling personal narratives describe a person overcoming the bad hand that fate has dealt him, not someone like me, who takes good cards and sets them on fire,” he writes early on in the book, and it barely prepares you for what’s to come.

He interviews family members and former friends still wary or spooked or damaged by their shared history, and his excavation into critical events that he may have been able to let time gloss over (or completely forget), including that enigmatic night of the gun, reveals as much about self-preservation as it does about the fickle mechanics of memory.

“If I said I was a fat thug who beat up women and sold bad coke, would you like my story? What if instead I wrote I was a recovered addict who obtained custody of my twin girls, got us off welfare, and raised them by myself, even though I had a little touch of cancer? Now we’re talking,” he writes. And yes, both versions are true.

In the end, you will like his story, a lot, and you’ll be grateful to him for telling it. And you’ll like him, too—not because of his folksy charm or because he was so great in that documentary or on CNN; his appeal in The Night of the Gun is earned only through the brutal personal assessment of an honest man determined to make sense of it all, for us, but also for himself.

Read more about David Carr:

Politico article by Jack Shafer

The New York Times article by A. O. Scott