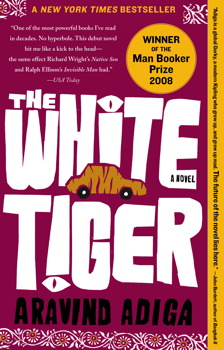

I have a friend, who when I first met him, seemed to only be able to read Booker Prize shortlist and winning books. Every reading group, when it came time for him to pick, he chose a Booker. Sometimes an Orange or a Whitbread prizewinner would sneak in but never a National Book Critics Circle or National Book Award winner. I felt his choices were downright un-American. But they were almost always good. One, The White Tiger, by Aravind Adiga has stuck with me for years and on revisiting it for this review I realized how much I missed the first time I read it and how much this book rewards a second and third trip.

A sort of a murderous Indian Gatsby without the thwarted love and the faux polish, Balram Malwi is a poor man who does whatever he must in order to break out of the lowly social caste and appalling life into which he is born.

He tells his own story – he cannot trust anyone else to tell the truth or portray him in the correct light – in a letter he writes over several nights to the Chinese Premiere on the eve of the Premiere’s visit to India. He writes under the blazing chandelier that hangs in the 150 square foot office of his new taxi service enterprise in Bangalore, land of the call centers. He wants the Chinese Premier to understand that, he, Balram represents the new India.

It could be a classic rags-to-riches story but that would be too trite. Balram is born to a low caste rickshaw driver and a mother who dies when he is young. So dispensable was he thought to be that he was not even given a name, only called “boy.” Another of the millions born each year scheduled to live his life in servitude and disappear quietly. It is a teacher who gives him the name Balram and who sees his intelligence and the promise that education offers him. But Balram is pulled out of school and made to work in a sweet shop as partial payment for a cousin’s dowry. It is in the sweet shop that his education really begins.

Exposed to the rampant corruption of Indian politics and the vicious indifference of the elite, Balram watches and learns and cagily makes choices that allow him to hopscotch over his family, friends and neighbors until he is in Delhi, employed as the driver to Ashok, the son of a corrupt local landlord, and his wife, Pinky Madam. What Balram does to achieve his final hop – at least the last one we know about – is absurdly logical even as it is morally repugnant and you will debate endlessly about whether it was justified.

Adiga is a brilliantly sly writer who uses Balram’s story to examine the society, politics, and culture in today’s rapidly changing India. He immerses you so fully in this world that when you look up from reading you are surprised to not be in Delhi, driving Pinky Madam through the maze of new housing developments or watching Ashok drink scotch with clients as they pocket bribes. At turns funny, alarming, horrifying and mesmerizing, you may not agree with Balram’s choices as he moves from the darkness to the light but you won’t be able to stop reading and you won’t be able to forget this amazing story.