There are some novels that stop you in your tracks when you realize they’re a debut. How can the writing be so nuanced, so concise, and yet equally packed with meaning? How does a first-time author capture a character’s emotional evolution as smoothly as they do larger themes about diaspora, mental illness, and family?

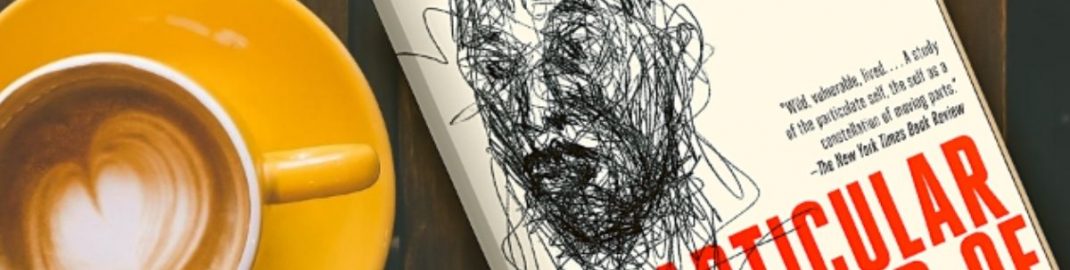

The only clear answer is it takes an exceptional and atypical writer for their first foray into long-form fiction to be as accomplished—and as widely acclaimed—as Tope Folarin’s A Particular Kind of Black Man, winner of the 2021 Whiting Award in Fiction!

Many coming of age novels follow young men as they face feelings of disconnection and uncertainty in their adolescence. For Folarin’s hero, Tunde Akinola, these experiences are even more keenly felt as a Nigerian-American child of immigrants living in Utah. Among a sea of white neighbors, Tunde’s family stands out, and at home, his parents try but fail to mask their unhappiness. Tunde’s father, an optimist who deeply believes in the American Dream, hits barrier after barrier in his search for long-term employment, while Tunde’s mother’s yearning for Nigeria draws her away from her husband.

When Tunde’s mother, who has begun to display signs of schizophrenia, eventually abandons the family to return to Nigeria, his ill-equipped father is left to pick up the pieces and rebuild a life for Tunde and his brother. His key guidance for his sons is to hold them to a higher standard than their peers, to choose “to be a specific kind of person. The kind of Black man who was non-threatening and well-behaved.” Thus, studying Sidney Poitier’s manner of speech and Bryant Gumbel’s interviews, Tunde trains himself to be what he and his father assume will be accepted by white society.

It’s only once Tunde reaches Morehouse College that he stops to evaluate how molding himself into his father’s ideal—a “successful and benign” Black man—may have shaped his self-perception and limited his identity. The narrative then takes on a more fluid, nonlinear style as Tunde begins to write about his life, meditating on the nature of memory and legacy and struggling with the possibility he might have inherited his mother’s mental illness.

Like his main character, Folarin is also the son of Nigerian immigrants who spent his childhood in Utah and graduated from Morehouse College. And like many debut novelists, he began by modeling a protagonist after his own life and experiences, here grappling with race in America and cultural identity, before letting Tunde’s world take on a life of its own. But whatever differences separate Folarin from his fictional creations, Folarin speaks in a 2019 NPR interview and elsewhere of his personal belief in the novel’s ultimate message, one that rings true from its core: everyone, regardless of who they are or who they think they should be, can write their own narrative.