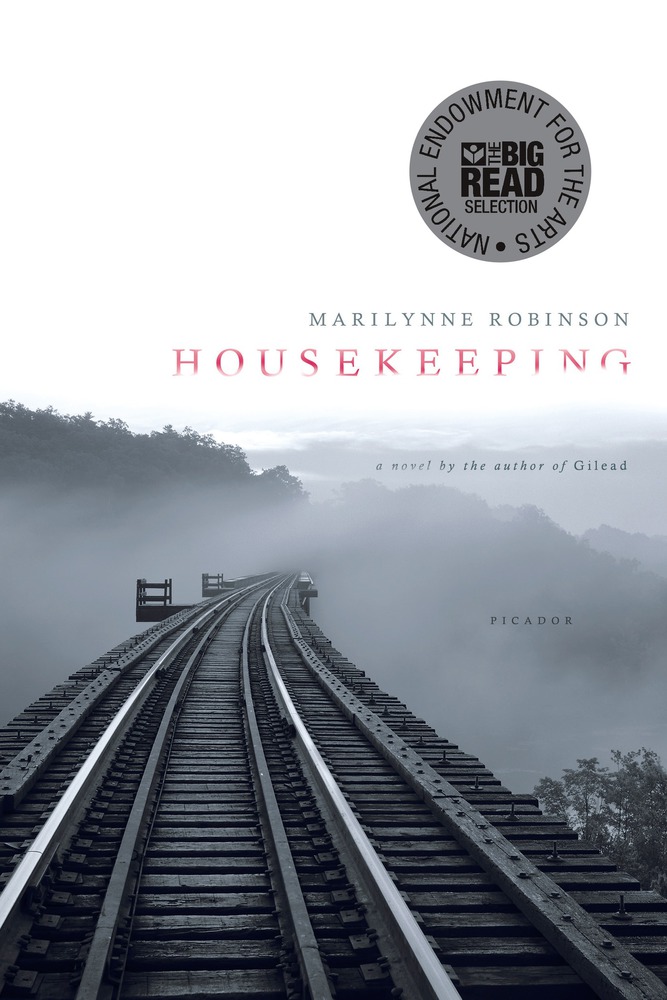

My love for HOUSEKEEPING developed backward. I saw the movie first, a default choice when the film I’d gone to see with a friend was sold out. We shrugged and went to the theater next door.

After the credits scrolled and the lights came up and the multiplex employees moved through the rows with their push brooms and garbage cans, we sat stunned, not wanting to break the spell.

So then, of course, I turned to Marilynne Robinson’s book, in a mix of exhilaration and despair. The former due to its sly transgressiveness in questioning the established order of things and to the underline-demanding beauty of its sentences; the latter because why even try to write when there’s that?

HOUSEKEEPING is the story of sisters Ruth and Lucille, who are abandoned by their mother in her hometown of Fingerbone on the shores of a vast inky lake surrounded by foreboding mountains in northern Idaho. Their grandfather lies below its waters—a victim of a train derailment—as does their mother, who after leaving her daughters sent her car soaring from a cliff into its depths.

The girls end up in the care of their aunt, Sylvie. She’s a wanderer recalled from riding the rails, whose indifference to social codes powerfully influences Ruth and proves just as powerfully off-putting to Lucille, who craves normalcy.

The girls end up in the care of their aunt, Sylvie. She’s a wanderer recalled from riding the rails, whose indifference to social codes powerfully influences Ruth and proves just as powerfully off-putting to Lucille, who craves normalcy.

Sylvie’s idea of housekeeping means dinner might consist of “watermelon pickles and canned meats, apples and jelly doughnuts and shoestring potatoes, a block of pre-sliced cheese, a bottle of milk, a bottle of catsup, and raisin bread in a stack.”

A reader feels for the younger sister. Who hasn’t been Lucille, cringing when the other kids point out whatever it is that makes one fatally different?

Although who, too, hasn’t been Ruth, pushing back against respectability’s claustrophobic restrictions? Why not jelly doughnuts at dinner? Why waste time with dull household chores when a lakeshore rowboat practically begs you to jump in and pull hard for a jutting point with its mysterious forests glittering with frost and promising fairy children?

And who hasn’t wanted to set one’s life afire, the house and possessions that represent safety and suffocation alike blazing defiantly in the night while judgmental neighbors watch. Then flee propriety, sprint onto the railroad bridge toward whatever lies on the lake’s far shore, the swirling danger of the black waters below, but ahead the dark irresistible unknowingness of freedom.

Over the years, as I’ve read and reread HOUSEKEEPING, it’s come to serve as a touchstone for me, a warning when I yearn for the safety of an ordinary sentence or a predictable book. Take the rowboat out onto the lake, I tell myself. Hop the train bound for unexplored territory. Run into the unknown, not in fear but in the exhilarating necessity of seeking the new.