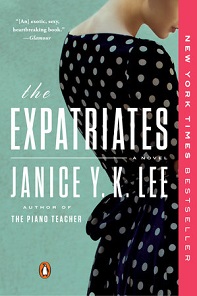

Two years ago, I packed up my suitcase and flew halfway across the world to live in Beijing for a summer. While I experienced all the classic tourist moments, what most struck me was that my time abroad revealed to me how much of my identity is based on my being an American. I became part of the local expat scene, frequenting joints known for their western crowds. I lived in Beijing, but specifically within a small, privileged sect of Beijing that was paradoxically both international and isolated at the same time. In her novel THE EXPATRIATES, Janice Y. K. Lee perfectly captures this strange sense of community and life in a foreign, yet oddly familiar, culture.

THE EXPATRIATES details the lives of three American women—Margaret, Mercy, and Hilary—whose lives converge and are ultimately changed forever in the cosmopolitan expat haven of Hong Kong. But it is clear that life abroad is far from the romanticized vision that many Americans believe it to be, as each woman grapples with the ghosts of her past and the promises of what might have been.

Hong Kong brings these women together, for better or worse—and as their stories of heartbreak, friendship, and motherhood unfold, they soundly reminded me that we are never quite as alone as we think.

For Margaret, the effortlessly beautiful mother of three and wife to a successful businessman, her insatiable grief stems from the disappearance of her youngest child on a family vacation in Korea a year earlier. In part to blame is Mercy, the recent Columbia graduate who Margaret employed to help watch over her children on the trip. Unsure of her future and still haunted by feelings of inadequacy that formed during her time at Columbia, Mercy is overwhelmed with guilt after the incident and withdraws from Hong Kong society. She lives in near isolation, cycling through temporary jobs and barely eating, until a chance encounter with a married man throws her back into the world she had exiled herself from. All the while, in another part of the expat neighborhood Repulse Bay, wealthy housewife Hilary struggles with what to do as her marriage crumbles following years of failed attempts to get pregnant.

Lee’s prose captures the overwhelming but strangely calming experience of displacement, portraying how it feels to live in a large, foreign city where you are constantly reminded of just how small a role you play. Each chapter switches focus between the three women, richly describing different facets of their personal grief and how they come to terms with what they cannot change.

While I don’t agree with all the choices that the women make, Lee’s moving character development makes it impossible not to root for each of them to succeed and overcome their individual hardships. These women reminded me, through Lee’s beautiful and riveting passages, of just how powerful female resiliency can be.