I tend to observe more than interact, a trait that makes me an avid people-watcher and people-listener, also known as an eavesdropper. My brain fills in the gaps of missing information, those things we usually can’t know about strangers—their thoughts, their motives, their pain, what they ate for breakfast, whether they’re cheating on their spouse, if their mother forgot to give them lunch money in grade school, if they laugh at dirty jokes, would they pat your back when they hug you, or would they hug you at all.

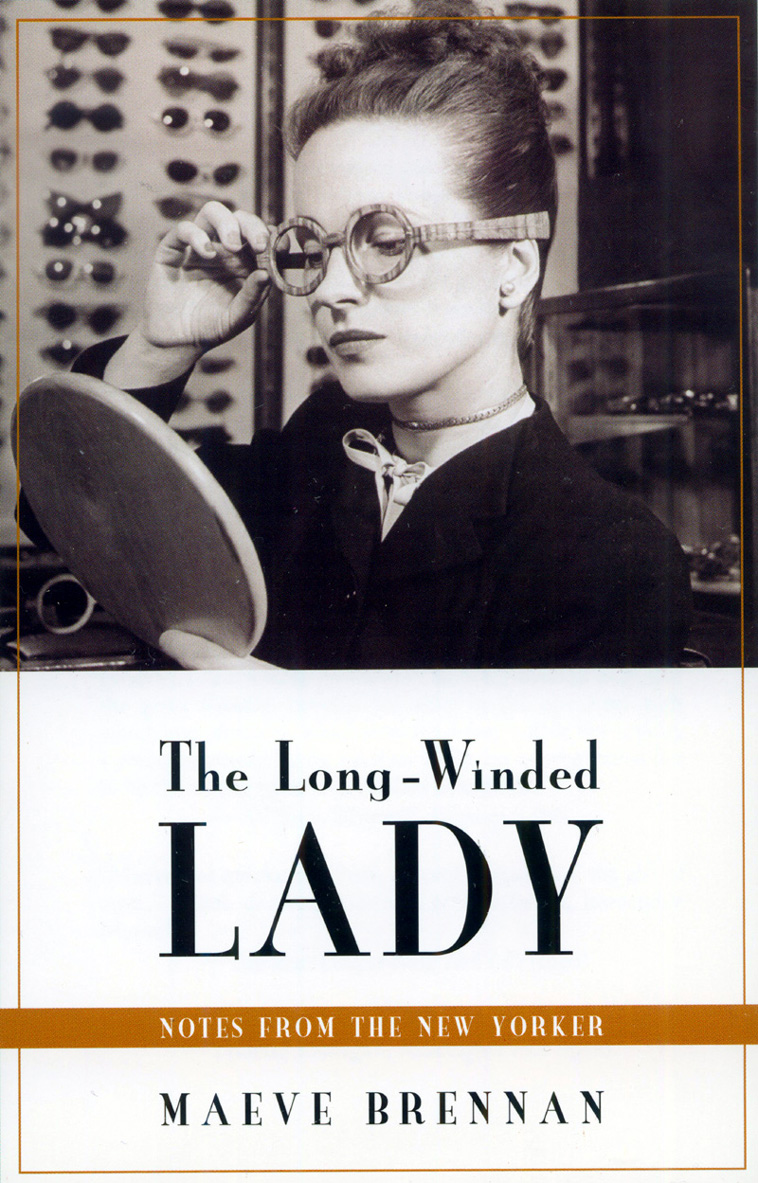

THE LONG WINDED LADY, a collection of Maeve Brennan’s ‘Talk of the Town’ columns published between 1953 and 1968, is the book form of my affliction. Brennan, also a people-watcher/eavesdropper, writes with a spirited observer’s eye, sketching vignettes of her life as an Irish expat making a living in New York City. Brennan’s exquisite renderings make reading these vividly-detailed observations of ordinary (and sometimes extraordinary) people moving through their days a visceral experience.

In “A Young Lady With A Lap,” Brennan describes one woman as “much too clever to wear a very short dress.” She goes on to note, “We all stared at her in our different ways, and from our attention she drew the air of indifference that made her a star.” Although Brennan rarely interacts with her subjects, her ability to watch a scene unfold, then provocatively snapshot the action, or lack thereof, leaves the reader feeling as if she’d witnessed the moment herself.

In “A Snowy Night on West 49th Street,” nothing much happens when Brennan goes to dinner at one of her usual haunts. Then again, it is the first snowstorm of the season, a gaudy woman she’s never seen before is at the bar, and an excited young secretary’s knee-jerk reaction to the bartender’s attempt at confidence brings an otherwise quotidian setting to life.

Whether enjoying a parade, pondering a “one-way” Manhattan, peering down on the street from her hotel window, or giving meaning to a spare stretch of city sidewalk, Brennan always finds someone or something interesting to behold. She observes not only how people look but how they act and interact and even how they think, ruminating on what she’s seen while blending it with her own acute awareness of human foibles. She deftly fills in those aforementioned gaps, always with a tendency toward the poignant. By the time her usually brief encounters are over, we’ve experienced a tale told start to finish, one that is possibly inaccurate, but its accuracy doesn’t matter in the least.

There is a sense of heaviness to most of these tales, and a quiet sort of unapologetic distance from the goings-on, a separation and autonomy that anyone who has ever been, or felt like, an outsider will recognize and understand. These forty-seven pieces vary in length, but all of them are quite short, making this a perfect book to be read slowly, in small bites, and savored.