There’s a moment in THE BEAUTIFUL BUREAUCRAT when Josephine—our heroine furiously battling the threat of unemployment through soulless data entry—is handed a plate of “kitchen sink” cookies. Her coworker offering them, one of two individuals she’s encountered in the bleak concrete building, surprises Josephine with this act of unexpected kindness, explaining she likes making the recipe because you don’t need to pick only one featured ingredient:

“I’ve been so torn about chocolate chips versus butterscotch chips, but here you don’t even have to choose! Walnuts and peanuts! Oatmeal and cornflakes! Raisins and dried cherries! Not to mention the shredded coconut. Sometimes we just need our freedom, you know?”

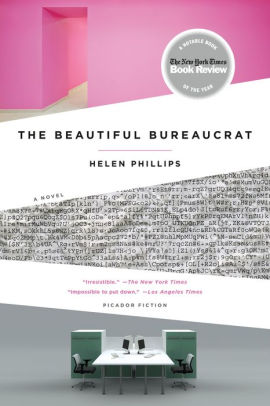

In THE BEAUTIFUL BUREAUCRAT, Helen Phillips makes the most of her literary freedom, putting her considerable talents to work in creating one astounding kitchen sink of a novel. Why choose thriller when you can use the pacing of a thriller? Why restrain the world to a dystopian future when you can highlight how our current world already echoes with dystopia? Why limit yourself when you can have satire and romance. Wordplay and sci-fi. Mystery and existentialism. “You don’t even have to choose!”

The office where this exchange takes place couldn’t be further from the cookies on offer. There’s no flavor, color, or options of any kind. There’s only Josephine’s windowless office, a new stack of gray files each morning on her desk, and the computer Database, where she aligns the files’ paper information—names and a seemingly incomprehensible jargon of numbers and letters—with their digital record.

Still, mindless typing is work, and she’ll take any work after nineteen months of unemployment. Plus, there’s hope somewhere down the line of a baby, and she and her husband Joseph—who is stuck in an equally monotonous administrative job he refuses to discuss—need jobs if they ever want to raise a family. In their previous lives, during which they lived in a suburban wasteland nicknamed “hinterland” for its oppressive lack of opportunities, the couple experienced their similar first names as a source for funny quips from others. But no one in this new, bleak city seems to notice moments of phonetic humor, especially not in her dreary office. Josephine alone makes games out of the monikers on her screen in a desperate attempt to make the hours pass quickly so she can get home to Joseph.

But as each day and each form presents countless new names, Josephine can’t help but begin to feel trapped by the plain office walls and long hallways of closed doors and shuffling, unspeaking bureaucrats. When Joseph doesn’t return one night to their cramped sublet, Josephine must confront the loneliness of a life without him and contemplate a world filled with only her 9-to-5 typing of strangers’ names into a computer, the purpose of which remains disturbingly opaque. Then, Josephine starts to recognize form names outside the office, leading her down a dangerous road of discovery.

Sometimes the very best pieces of art are the ones most difficult to describe. Your tools are only broad genres and abstractions, sparked with the vivid details you hope others find as unforgettable as you do: the menace of a missed postman, the sticky sweet craving of black licorice, the crash of a breaking heirloom, or the devastating comfort in a diner waitress.

Like Josephine struggling with the right words to thank her coworker, the most apt description may simply be a heartfelt appreciation for what you didn’t know you needed:

“This is the food I’ve always wanted to eat.”