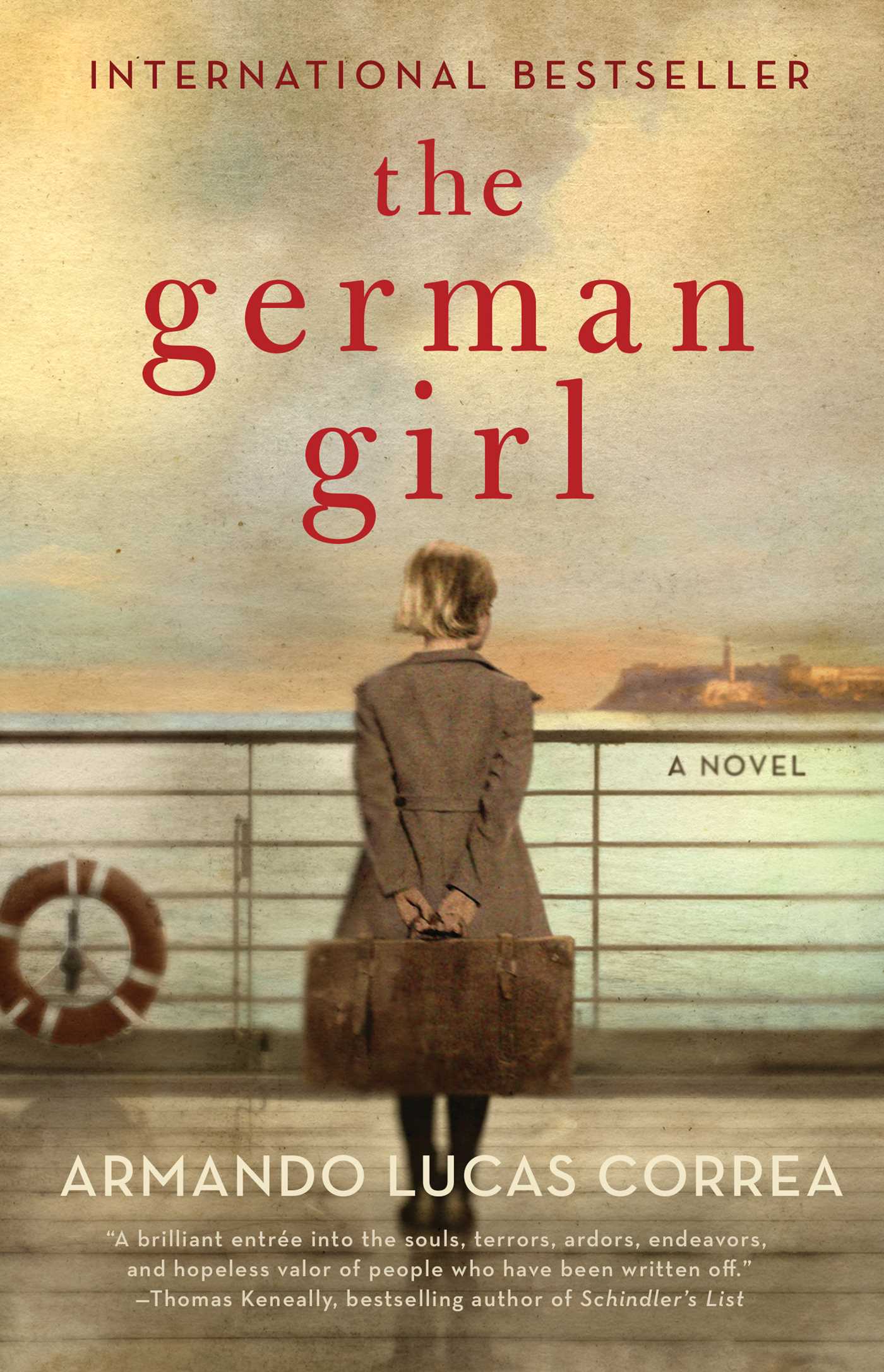

As a lover of history and historical fiction, I dove into Armando Lucas Correa’s THE GERMAN GIRL on a recommendation and was eager to read about Hannah, a Jewish girl who lives in Berlin in 1939. It was different from other books I’d read in this genre, and stood apart in its quest to weave together two tales of loss and family and to carefully examine what it means to be a survivor.

Hannah and Anna, two 12-year-old narrators living in different countries 75 years apart, are both lost. Each is unaware the other exists, though they are connected by a family history scarred by loss. Hannah’s narration focuses on her family’s attempts to flee Germany and her life as a refugee over decades. Hannah’s family goes to incredible lengths to secure passage out of Germany, only to be turned away from Cuba, the United States, and Canada when they arrive. They spend the rest of their lives in Cuba and struggle with their identities and loss of loved ones.

Anna, born and raised in present-day New York, has never known her father and cares for a mother who has been severely depressed since he died. Anna gives a voice to the present, and we learn details about her connection with Hannah and what happened to her father. It’s revealed that Hannah is Anna’s great-aunt—her deceased father’s only living relative. Anna knows nothing about her father or his family history, and through Anna’s story, the secrets of Hannah’s past begin to unravel. As Anna learns, so does the reader; the aha moments and slow reveals make this story an incredible and emotional one, and I am not embarrassed to admit I cried more than once.

THE GERMAN GIRL is a historical fiction, but doesn’t focus its attention much on the past. Hannah’s stories have a fog over them, and her sad but acute perspective is passive even as she observes war, betrayal, and love. This monotony of the past, the constant feeling of lost hope, defines the story. THE GERMAN GIRL is unique in that we know from the beginning that our narrator Hannah has no hope, while our narrator Anna has just begun to find some. We know the endings to the stories they’re telling us, because we know the historical events surrounding the St. Louis, the ship that Hannah and her family board in 1939: it was famously turned away amid a growing crisis in Europe. Once Hannah and her mother are safe, they build an isolated, bitter life in their new country, and I found that I was angry with her for not trying, for losing hope instead of attempting to build a better life. It made her connection with Anna even stronger, and I clung to Hannah’s last hope for a brighter future, even if it was for someone other than herself.

But I think the past, in this story, is both very much the point and not the point at all. THE GERMAN GIRL made me ask myself if I really believe that one can ever truly leave the past behind and cede control to pain that’s far beyond our reach. The emotional impact comes from a slow, poignant realization that nothing that is done can be undone, and moving forward can often be impossible. Somehow, Correa makes this idea a profoundly hopeful one, in knowing that despite the past, the future continues, undaunted.

The last pages of THE GERMAN GIRL contain the passenger manifest from the St. Louis. I knew the end of the story. Still, I cried.