My husband and I met at work, and for two years we kept our relationship a secret in the office, assuming that if we ever broke up our discretion would help avoid some awkwardness with our coworkers. When we tell people that, they imagine it as exciting and sexy: sneaking around for in-office trysts. But in truth, hiding our relationship was stressful and annoying. We lied to our colleagues, stood in awkward silence in the elevator, locked down our Facebook privacy settings, and entreated friends and family to never post a photo of us together. The reality isn’t always the best story.

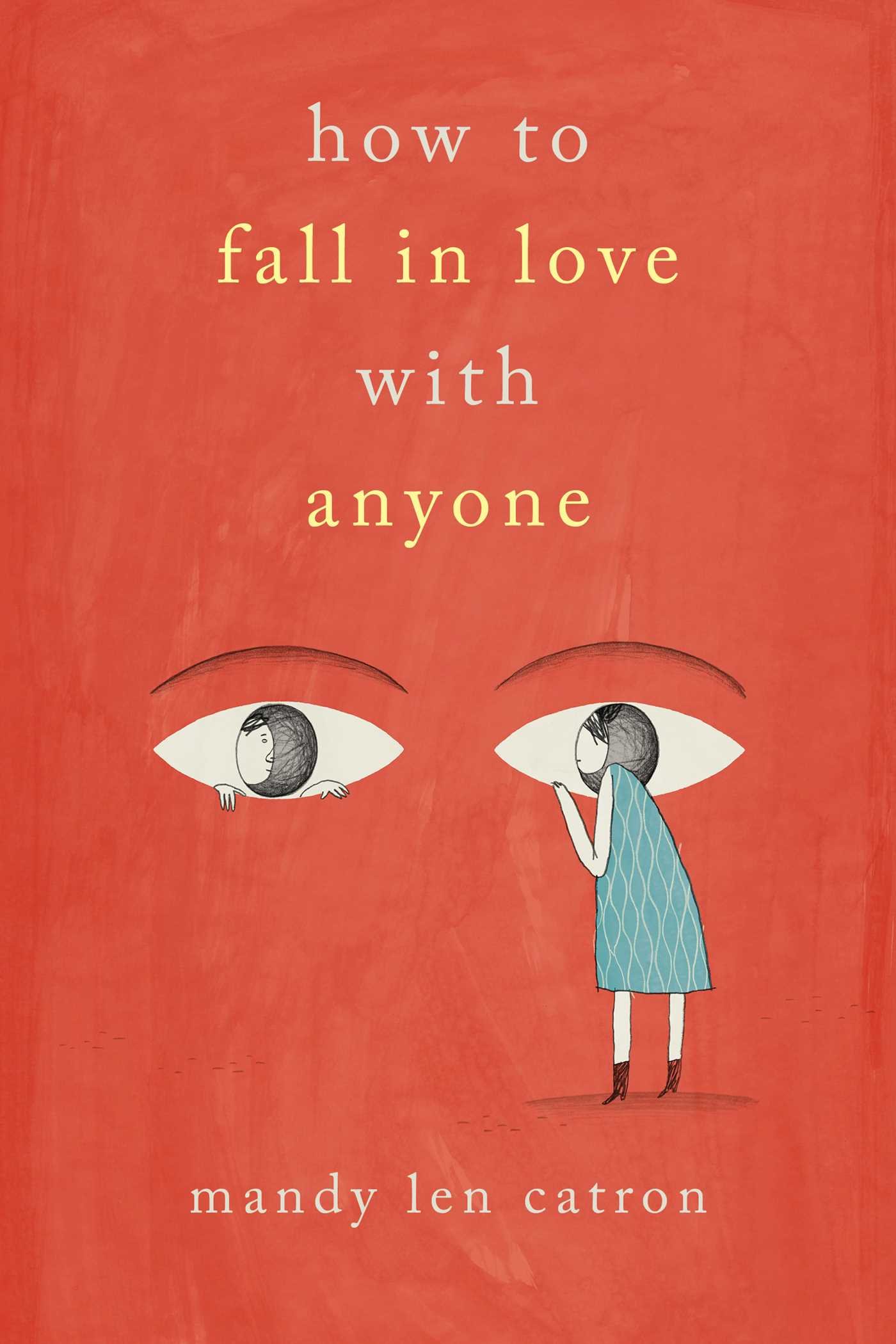

The difference between love and love story is the basis for Mandy Len Catron’s book, HOW TO FALL IN LOVE WITH ANYONE. It was inspired by her Modern Love column, “To Fall in Love with Anyone, Do This,” one of the most-read New York Times pieces of 2015, about a psychological study designed to create romantic love in a laboratory, and how she tried it with an acquaintance. The book, however, is much more complex than the essay, a beautifully written and well-researched cultural criticism as well as an honest memoir. It’s about the dangers of love stories, the nature of storytelling itself, and the realities and fictions of real-life love. From Sixteen Candles to Rent, and from her small Appalachian hometown to her current life in Vancouver, Catron analyzes our cultural stories as well as her own.

The crux of Catron’s years of research is this: love stories are problematic, setting up unreasonable expectations about the importance of acquiring love and how to go about it. “If I believed that some kinds of love stories were dangerous—particularly stories that ignored the hard parts—then I shouldn’t go around telling them.”

And yet, neither she nor I—or anyone—can shake the impulse. We create our own stories because it’s expected, because it’s the way we recount our lives. We tell them to ourselves, we tell them to others, we tell them at weddings and to our kids and, eventually, at funerals. But in the act of telling, the stories become both more and less real.

Each of Catron’s essays are backed up by psychology, history, and science on the nature of relationships. Through her research, she explains that dating as we know it is new, as is marriage. That our culture’s obsession with partnership isn’t ingrained, but a recent convention. And so we’re left wondering, what’s the big deal? How important is love anyway?

Catron is at her best when she’s telling her own story: discovering how to be a partner, how her own relationships work or don’t, and what all of this research means to her. It’s through Catron the person—the daughter and the girlfriend, not just the researcher and writer—that the power of love and its narrative is truly felt. Even while she (and we) recognizes the problems with love and love stories in our culture—true love is mundane, marriage is socioeconomic, love stories aren’t real—their influence is impossible to ignore. Even as she critiques rom-coms and researches the biological bases for love, she still recognizes its power. We can’t extricate ourselves from it, even if it is painful and problematic, even if it is untrue and unhelpful.

And yet, the book functions as a love story in itself. It begins as she’s ending a relationship, then she comes to terms with being single and considers the history and nature of love. Throughout, I wonder if it will work out for Catron, all while learning that the very notion of “working out” is a fallacy. I hope, despite myself, that she’ll find someone, and eventually she does. It’s not necessarily Happy Ever After, but the end credits roll. And there’s nothing wrong with that. But there’s also nothing inherently right about it either.