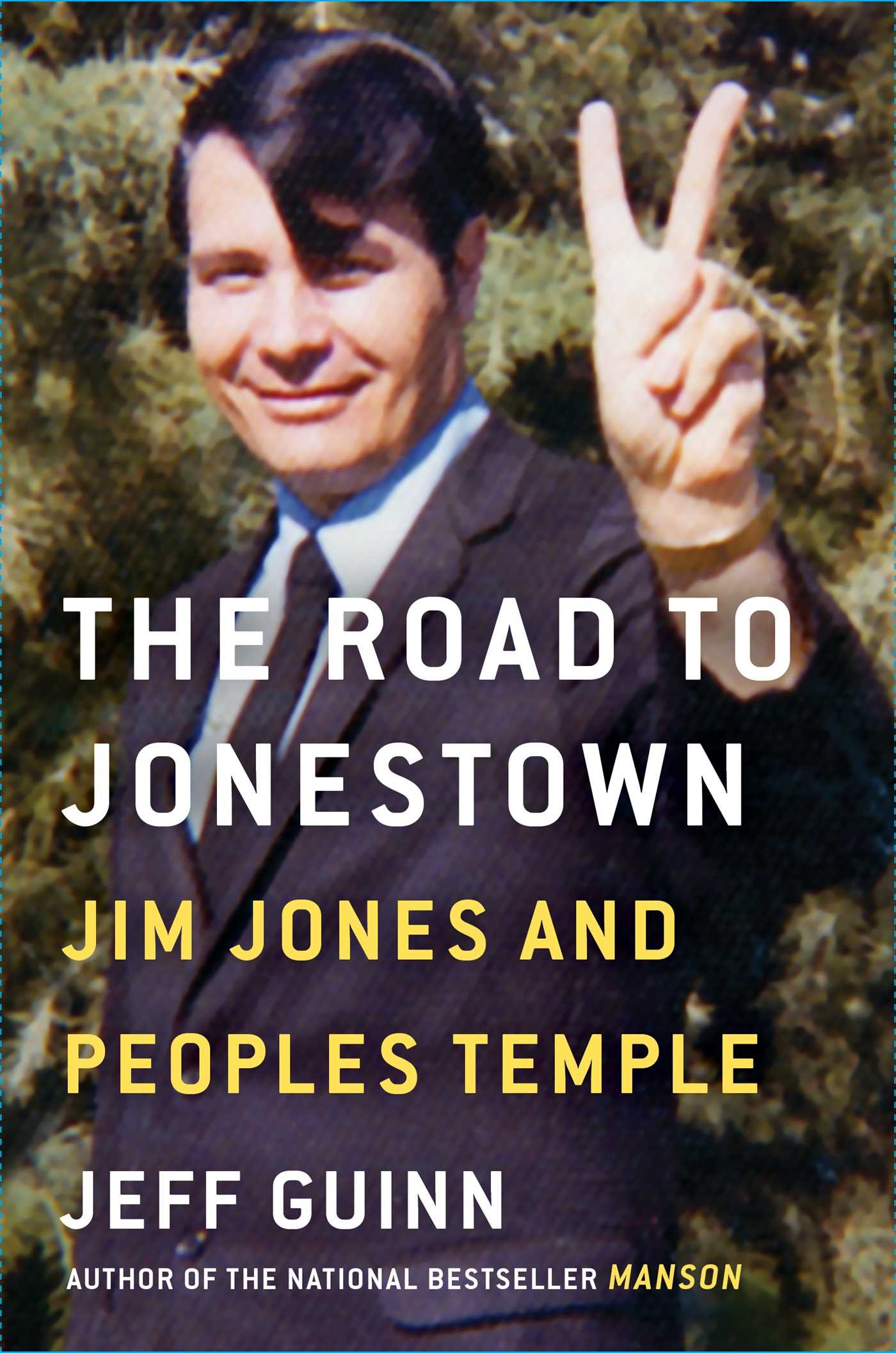

My friend Richard and I have a little book club together at work. It goes like this: when he is coming to or leaving the office, Richard is often carrying the book he’s reading and I ask him how it is. If he’s enjoying the book, sometimes he’ll lend it to me when he’s done and then we discuss. The club works great for me because he reads a lot of history and biography, genres that I would seldom pick up otherwise. Richard’s latest book club selection was THE ROAD TO JONESTOWN: JIM JONES AND THE PEOPLES TEMPLE by Jeff Guinn, a blend of biography and true crime that had me hooked from the very first page.

I’d of course heard the expression “Don’t drink the Kool Aid” before, but had no idea where it came from until I read this book. Guinn chooses to start the story at the end, with the gruesome 1978 discovery of the Jonestown tragedy: several victims, including a US senator, murdered on an airstrip and more than 900 people dead from drinking a cyanide-laced powdered drink, some willingly and some by force, at the order of their religious leader, Jim Jones. But how did that many people come to be living in a settlement deep in the Guyanese jungle? Who was this preacher they were following, and why would he give such a terrible order? Guinn pursues these questions in an expansive, detail-oriented, impeccably researched chronicle of the road that led not only Jones, but also his family and followers, to that horrifying day in the jungle.

What I enjoyed most about the book was that the author approaches each of the characters—from Jones to his family to his followers—in a nuanced way. He presents Jim Jones’s many flaws, like his egotism, drug problem, obsession with control, and eventually his paranoia and erratic cruelty. But Guinn also examines his early career, when he preached socialism and racial equality to his diverse congregation in the late fifties and early sixties and lead Indianapolis’s Human Rights Commission—working hard to bring about the integration of restaurants and stores in his city.

Guinn portrays Jones’s many followers with equal detail and respect. It would be easy to dismiss the 900 people who followed Jones into the jungle as brainwashed sheep, but Guinn makes a careful study of their reasons and motivations, skillfully turning such a massive number of people into a group of individuals. Some followers gradually came to believe Jones’s claims that he was God, or at least a powerful prophet. Some followers didn’t believe that at all but were willing to overlook his more outrageous claims because they believed so deeply in the Temple’s mission of promoting socialism and equality, and of helping others in need.

Jeff Guinn leaves his readers with a question that is a thread throughout the book: “Was Jim Jones always bad, or was he gradually corrupted by a combination of ambition, drugs, and hubris?” The question, as Guinn says, is unanswerable, but THE ROAD TO JONESTOWN left me pondering the nature of evil for weeks. Until Richard’s next book club pick, that is!