I’d just sat down to put the finishing touches on the introduction to my book, IT TAKES ONE TO TANGO—a self-help book about marriage—when I heard the teaser for an upcoming interview with Jessica Lamb-Shapiro on “Fresh Air.” She’d written a book called PROMISE LAND: MY JOURNEY THROUGH AMERICA’S SELF-HELP CULTURE, and from what I picked up in the sound bite, it seemed that she and Terry Gross were about to make light of me, my readers, and the book I was about to package up and send out to publishers.

Fine, I thought. Better to know in advance what the skeptics will say.

PROMISE LAND, it turns out, is neither an indictment nor an endorsement of self-help workshops and books. It is a thorough, thoughtful history of the genre, a laugh-out-loud funny, deeply touching story about how the author—a self-help skeptic—found plenty to poke fun at in the self-help culture, but also found a handful of things that (true to the promise of the self-help genre) dramatically changed her life.

I’ve always believed that the best things in life come to us by serendipity. We set out in search of one thing and accidentally stumble upon something that turns out to be much more valuable to us than what we’d sought in the first place. So it was for Jessica Lamb-Shapiro as she explored the highs and lows, the pie-in-the-sky promises, magical thinking, outright falsehoods, and points of wisdom that overflow the self-help bookshelves.

Jessica tackled the subject of self-help first as a researcher, then as a “civilian”—a person who, like the rest of us, has some thorny issue, some unfinished business that self-help books can, well… help us address. She’d read her way through every possible in-need-of-help book there is, from debting to dating—she’d even walked on hot coals.

Then she found herself smack up against the one subject she’d avoided all her life: the grief of losing her mother when she was a young child. Jessica’s father himself was unable to grieve, so grief—and the very details of her mother’s death—remained untouched and unspoken between them until, in the course of writing the book, she became ready to address them.

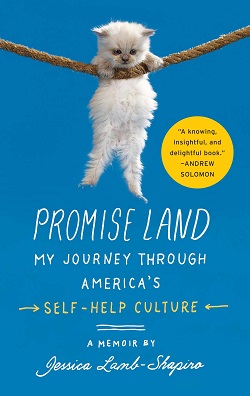

Her story is, in the end, a love story, a story of things lost or broken somehow made whole by facing that which we are afraid to face. And no, not in ten simple steps or in one giant leap. And not in a fake, smiley-face, “it’s all good” kind of way. In fact, unlike the “hang in there” cat on the cover, in the end she discovers that good things also happen when we let go.