Editor’s Note: Nan Graham is the Publisher of Scribner and the editor of Frank McCourt’s memoirs, ANGELA’S ASHES, ’TIS, and TEACHER MAN. Today we are celebrating the twentieth anniversary of the publication of ANGELA’S ASHES on what would be Frank McCourt’s eighty-sixth birthday.

One day in the spring of 1995, when Frank McCourt was sixty-four years old, I received a box from literary agent Molly Friedrich, containing the first 159 pages of the memoir ANGELA’S ASHES. Several of us read the pages, as Frank would say, with alacrity. And loved them, swiftly seduced by the opening sentences: “When I look back on my childhood I wonder how I survived it all. It was, of course, a miserable childhood; the happy childhood is hardly worth your while.”

Who had ever written about poverty, religion, class, hypocrisy, love, tragedy, and hopelessness with the exuberance and compassion of Frank McCourt? We were hell-bent on publishing ANGELA’S ASHES. But, we wondered, would this retired New York City school teacher have the stamina for a two-week book tour? We wanted to meet him.

Frank came into the Scribner offices that week and, yes, he had a twinkle in his Irish eyes, and a glorious blue shirt, and his charm was all sparkle and mischief.

“A two-week book tour? Talking to people who choose to be in the room?” he asked. “Six times a day, five times a week, I had to seduce thirty-five sullen, hormone-raging high-school students who wanted to be anywhere but in the classroom.” (His book tour lasted ten years.)

We acquired the rights to ANGELA’S ASHES and, six months later, on November 30 (Jonathan Swift’s birthday, he told us), Frank appeared with another box containing all 459 manuscript pages. And the magic began.

Our sales reps and the booksellers fell in love, as we had. The New Yorker wanted an excerpt from this story about an Irish family that immigrates to Brooklyn during the Depression and then returns to Ireland where the poverty is even worse. Frank was profiled for the cover of the New York Times Magazine—to catch readers up on his adult life, since ANGELA’S ASHES ends when he is nineteen years old.

Our first print was modest. A few months after publication, we had a million hardcovers in print. And then two million.

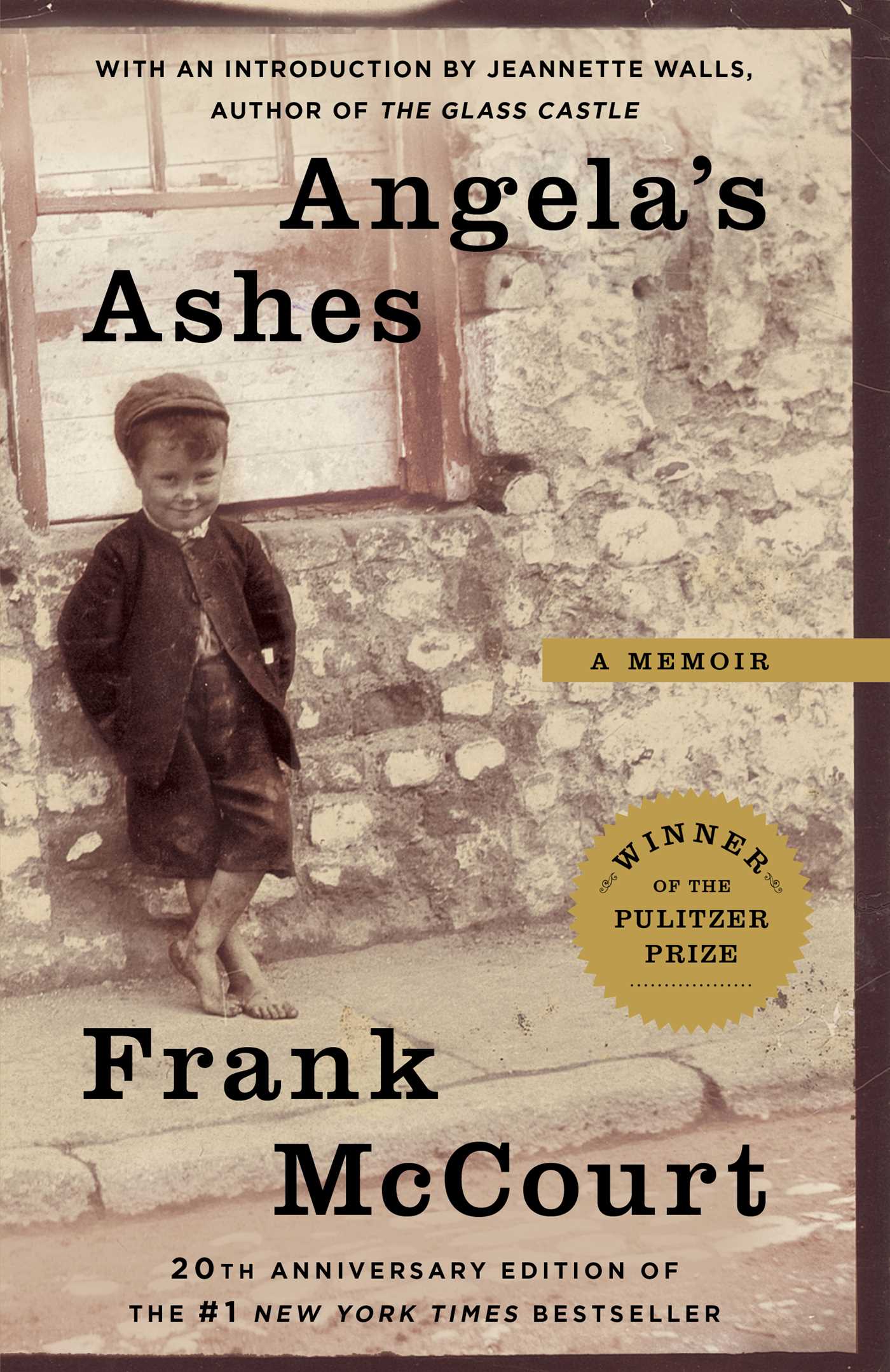

ANGELA’S ASHES was a #1 New York Times bestseller. It won the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Critics Circle Award, and the Los Angeles Times Prize, and was on just about every best books of the year list in the country.

“I didn’t know you could write about yourself,” said the magnificent McCourt, who ushered in the Age of the Memoir. More enduringly, he told readers everywhere that there was no shame in poverty and that storytelling helps us survive and transcend.

As Jeannette Walls writes in her gorgeous introduction to the twentieth-anniversary edition of ANGELA’S ASHES, Frank’s father drank the meager wages and the dole money, left his children and wife in direst poverty and hunger. But his storytelling transformed a world that was heartbreakingly grim into a place that was sometimes full of wonder. And he gave Frank his gift.

“Stock your mind, stock your mind,” says Mr. O’Halloran at Frank’s school in Limerick. “It is your house of treasure and no one in the world can interfere with it. You might be poor, your shoes might be broken, but your mind is a palace.”