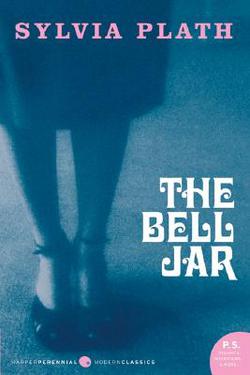

During my academic career I read all the coming-of-age greats—The Catcher in the Rye, A Separate Peace, The Giver, Lord of the Flies, even Into the Wild—but female-driven narratives were conspicuously missing from assigned summer reading lists and liberal arts syllabuses. It wasn’t until three years ago, trolling for something to read on my parents’ bookshelf one lazy Thanksgiving, that I first picked up Sylvia Plath’s classic novel, The Bell Jar.

“Oh, that’s such a sad book,” my mother sighed when she saw me skimming its yellowed pages.

But it certainly didn’t seem sad to me when I curled up on the couch and began to read. There was a tenor to the prose that was both funny and fuming, incisive and all knowing. I could relate to the paralysis that impending adulthood induced, especially from the perspective of a girl like Esther Greenwood, who, as she enters her senior year of college, seemingly has the world at her feet. She makes top grades at an elite college, has landed a competitive internship at a prominent women’s magazine in New York City, and is dating a nice, boring guy who will surely make a nice, boring husband. In 1960s America, the height of suburban rhapsody, what more could a girl want? Only Esther wants none of it, and it becomes increasingly evident that this is no run-of-the-mill apathy—she is lapsing into a severe depression. Esther attempts to take her own life and nearly succeeds, which lands her in a mental institution for the third act of the novel. Some consider The Bell Jar a roman à clef, as Esther’s struggle with mental illness parallel’s Plath’s own. Esther, however, survived her episode.

But my mother was also right. There are certain moments that are so sad I felt as though someone were tightening a belt around my heart to the narrowest possible notch (“I laid my face to the smooth face of the marble and howled my loss into the cold salt rain”). Still, sad wasn’t the taste The Bell Jar left in my mouth once I turned the last page, just before the Thanksgiving turkey was served. It’s certainly not what’s kept me coming back to my favorite passages time and time again, either.

What The Bell Jar left me with was a sense of camaraderie. I’m fortunate that mental illness has never touched my life or the lives of those I love, but I have my own bell jar, the glass infused with the angst and expectations unique to one of the most banal but insidious processes there is: growing up a girl. Growing up a girl doesn’t seem to have changed much since Plath came of age in the 1950s. I’ve been instilled with an aspiration to get married and have children, even though I’m extremely ambivalent about one of those things. I have also dedicated many hours to performing every woman’s civic duty of berating herself for not being a thinner, prettier, and nicer version of herself.

I’m not a depressed person by any means. Most days, unlike Plath, I feel “my lungs inflate with the onrush of scenery—air, mountains, trees, people. I [think], ‘This is what it is to be happy.’” On other days, the bell jar descends, forcing me to “stew in my own sour air.” I cancel dinner and drinks plans with friends (worrying that I’m far too fat for such caloric good fun). I’m seized by a panic that, at thirty-one, I’m not where I’m supposed to be in life.

I tend to revisit The Bell Jar when I’m feeling sad, but not because I’m looking for something dreary to match my dark mood. I read the passages to feel comforted and understood, to listen “to the old brag of my heart. I am. I am. I am,” and know that I am, too, only not alone.

Jessica Knoll is the author of the New York Times bestselling novel, Luckiest Girl Alive.