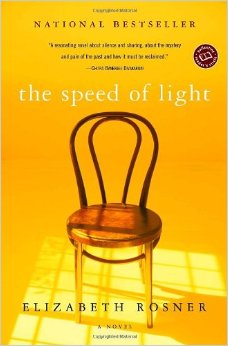

Novelist, poet, and essayist Elizabeth Rosner is the author of the highly acclaimed bestselling novels The Speed of Light and Blue Nude. Her newest novel, Electric City, and Gravity, a poetry collection, were both published in October 2014. Her website is www.elizabethrosner.com.

The release date for my first novel, The Speed of Light, was Tuesday, September 4, 2001, and the following Tuesday was meant to be the first day of my national multi-city book tour. By the time I was wide awake and giddily preparing to depart for the Oakland airport, the World Trade Center was billowing murderous smoke into the sky, and my Manhattan publicist was calling to tell me to stay home. The rest of this story is much more than obvious; my personal grief was miniscule compared to the epic size of the losses all around. The unmistakable Before/After threshold of that day has persisted all these years, and will undoubtedly remain true for a very long time to come.

Despite a canceled book tour and a mood of despair that threatened to eclipse anything remotely creative, it turned out that I myself, like so many others, needed to find meaningful inspiration for optimism and redemption. As a daughter of two Holocaust survivors, I had written about the destructive impact of silence and isolation. Yet my novel’s three characters, each uniquely impacted by a traumatic past, all found a way toward healing. The Speed of Light was translated into nine languages, received numerous prizes and awards, and was even optioned for development as a feature film (not yet made). Readers all over the world welcomed the message of human connection in the face of tragedy and grief, the commitment to the power of storytelling as a means for hope.

By some near-mystical coincidence, perhaps, the first sentence of the book reads: “The changes began on a Wednesday. Miércoles, the day that sounds like miracles.”

The Speed of Light is the story of siblings whose father was a Holocaust survivor—Julian, a recluse, and Paula, an opera singer as adventurous as her brother is shy—and Sola, the only survivor of the government-sponsored massacre of her small Central American village. The interwoven narrative moves in a gradual arc from sorrow into song. Even now, more than thirteen years past its original publication, I continue to receive notes and messages from strangers who consider my novel to be one of their favorite books “of all time.” They tell me that it speaks to their deepest belief in the way darkness can ultimately yield to light; they thank me for showing that hard-won beauty and even love are available beyond the endurance of nightmares. They send me gracious letters, and they approach me in bookstores where I’m signing copies of my newer publications. They tell me over and over that my words matter, that my story has remained in their hearts, that they will never forget Julian, Paula, and Sola—their braided journeys of recovery.

I hardly know what to say when I receive these acknowledgments. Because in truth, what I’ve come to believe about the most powerful forms of writing is that the author is not herself entirely responsible for it—not only in the sense of its creation but in the effect it may or may not have on other people in the world. At my best, I was writing The Speed of Light in a state that can only be described as a state of grace.

Indeed, it was not “my best” so much as it was my being as wide open as possible to receive and transmit. The brilliant improvisational pianist Keith Jarrett once said that there was a period of time when the magnitude of what was being poured through him actually “broke the vessel.” He spent a few years in such absolute physical (and spiritual?) exhaustion that he couldn’t play or perform at all. I’m reminded too of the final lines of Virginia Woolf’s masterpiece To the Lighthouse, where we see Lily Briscoe in the precise moment of finishing her painting: “Yes, she thought, laying down her brush in extreme fatigue, I have had my vision.”

Am I exhausted? I hope not. (Tentatively, oh so tentatively, I have begun to imagine a new novel.) I sometimes joke that I’m the slowest writer on earth. (The Speed of Light took me ten years to write; my most recent novel, Electric City, took eight.) What I really mean is that words and stories and characters come to me at a pace I cannot control or accelerate. Julian materialized in my imagination as a troubled young man in an apartment with eleven televisions; I wanted to discover what was so frightening to him about the world, and what might help him feel safer. Little by little, his sister’s operatic voice found its way into my inner ear, and Sola’s presence bloomed with a fragrance all her own. Page by page, I’m in service to something much larger than myself, and it feels as though I can only practice the art of staying available and ready.

In a time when the blissful oblivion of reading fiction seems under siege more than ever, threatened by the infinite stimulations and distractions of the so-called “real” world, I want to express a profound gratitude for those who willingly turn their attention to books. Turning pages one at a time, whether touching pages or screens—this small action at one’s literal fingertips!—in my view this is an act of faith in the human spirit, a placing of trust in the potency and vitality of language and imagination to bring ourselves into contact with others who may be deeply familiar or exquisitely strange. This may just be one of the purest ways to bring us together, one by one, and to create the possibility for peace.