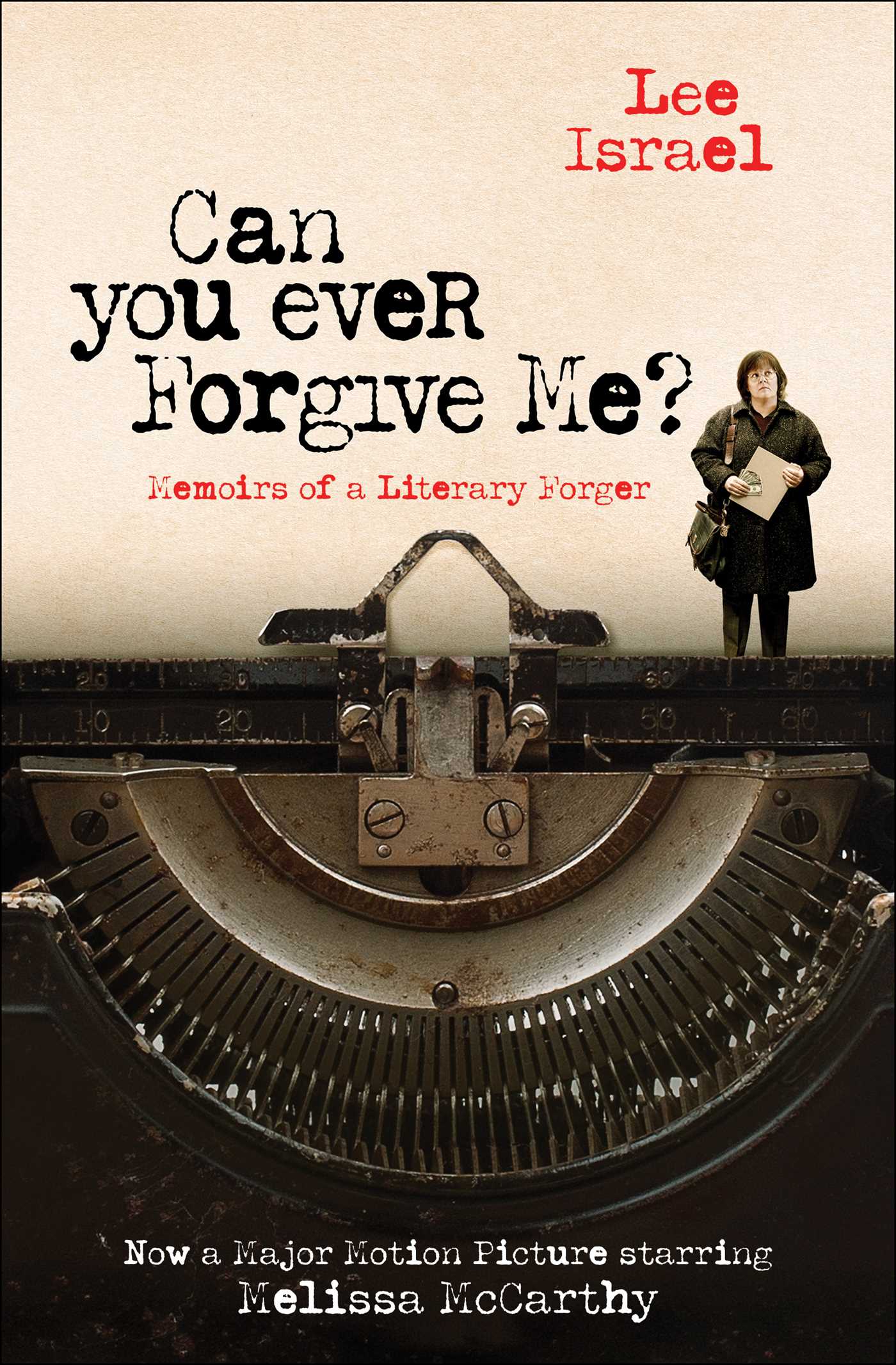

Working in publishing, one sees as fair amount of imitation, both good and bad. Authors model their own work after the books they love, or those that they feel have sold well in the past. It sometimes leads to disaster, but often it is a pleasure to read and engage with, if not for the content than at least for the intention. After all, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, right? Never have I seen this made more abundantly clear than in Lee Israel’s Can You Ever Forgive Me?, a short but sweet memoir about one woman’s days as a forger of literary letters.

It’s a story that reads like any other crime narrative. A person is down on their luck, trying to make ends meet, and picks up a questionable hobby that gets them on the wrong side of the law. But, here’s what makes Can You Ever Forgive Me? turn from criminal to almost comedic: Israel was a New York Times bestselling biographer, on contract with a major publishing house and in possession of serious respect for historical accuracy. For about a year and a half in the 1990s, she created hundreds of reproduced and fabricated celebrity letters that were sold and traded by major dealers across the country, going for thousands of dollars.

Still, though she’s breaking a number of moral and actual laws, Israel’s focus remains on making factual forgeries. She spends hours in New York’s libraries reading biographies of her subjects, making sure that dates match up, vocabularies are realistic—she even used statements or opinions the supposed author was on record as saying in different moments. She addressed the letters to people who were known to be associated with the author, so that it wouldn’t be impossible that such a conversation would exist. In some cases, she traced the signatures of the letters or copied the letterhead right out of the archives. She noted spaces between words, comma placement, feasibility of impersonation (Walt Disney was an absolute no-no, since “his signature looks like something underneath the Articles of Confederation”). In some cases, she took the original letters from libraries and replaced them with her forgeries so she could have more time to perfect her craft. Some of her most popular writers were Noël Coward, Dorothy Parker, Louise Brooks, and Edna Ferber, all of whom were dead by that point and couldn’t confirm or deny authenticity. Two of the Coward forgeries were so convincing, they were included in 2007’s critically-acclaimed collection The Letters of Noël Coward. The perfect crime? It just might be.

That is, until some began to suspect the letters were fake, mostly because she began to add veiled references to Coward’s homosexuality in some letters—something he never discussed during his lifetime. Word spread like wildfire among the private collection community and libraries who were confused about the sudden lack of authenticity in their copies of some letters. Authorities got involved, and after being sold down the river by an associate, Israel was brought down in a sting operation. She pled guilty in 1993 and was sentenced to half a year of house arrest and five years of probation. Ever the hustler, though, she managed to find a lot of work as a temp for magazines (she didn’t have to report her legal history).

When I picked up this book, I wasn’t entirely sure it was for me, though I was intrigued how a memoir about such an interesting subject could fit in 127 pages, especially when some of those pages are just photos of the forged letters. It turns out that with Israel’s wit, 127 pages is all you need. It’s laugh-out-loud funny and compelling. As it was in her line of business, the subjects are more important than she is, taking center stage while somehow leaving us with a surprising amount of insight into Israel’s life. It was the perfect armchair escape, only taking about an hour to read and making me feel like I was in on some clever conspiracy, without any risk of jailtime.

If you’re still wondering how Israel was able to get away with this, look no further than a particularly hilarious part of the book, midway through, when she forges her own book contract—she was slated to write a book about the cosmetics mogul Estée Lauder—to state the upcoming title as “A WORK PROVISIONALLY TITLED AUTHORS AND ALCOHOLISM,” which gained her access to the personal collections of Faulkner and other notoriously scandalous writers. When she asks to see Gone with the Wind author Margaret Mitchell’s letters at Yale, however, she’s reminded that Miss Mitchell did not have a drinking problem. Her response? “I answered that I was also investigating the writers who had managed to maintain their sobriety in a field littered with cirrhotic livers.”

That, my friends, is how it’s done.