Today, we’re happy to bring you something written by Anthony Doerr which you’ll find at the newly-launched Scribner Magazine. Mr. Doerr is also the author of Memory Wall and Four Seasons in Rome.

I first saw Saint-Malo while I was on book tour in France. It’s a ghostly, imperious walled city in Brittany, surrounded by emerald green sea on all four sides. It was night, and after dinner I went for a stroll on top of the ramparts, peering into the third-floor windows of houses, the low-tide beaches glimmering in moonlight, the town glowing. I felt as if I was walking through a city plucked from the imagination of Italo Calvino, a place that was part fairy-tale castle, part M. C. Escher drawing, part mist and ocean wind and lamplight. You walk its cobbled lanes, you smell the tides, you hear the echoes of your footsteps, and you think: this city has survived for well over a thousand years. But Saint-Malo was almost entirely destroyed by American artillery in 1944, in the final months of World War II, and was painstakingly put back together, block by granite block, in the late 1940s and early 1950s. That a place could so thoroughly hide its own incineration, and that my own country was responsible for that incineration, fascinated me.

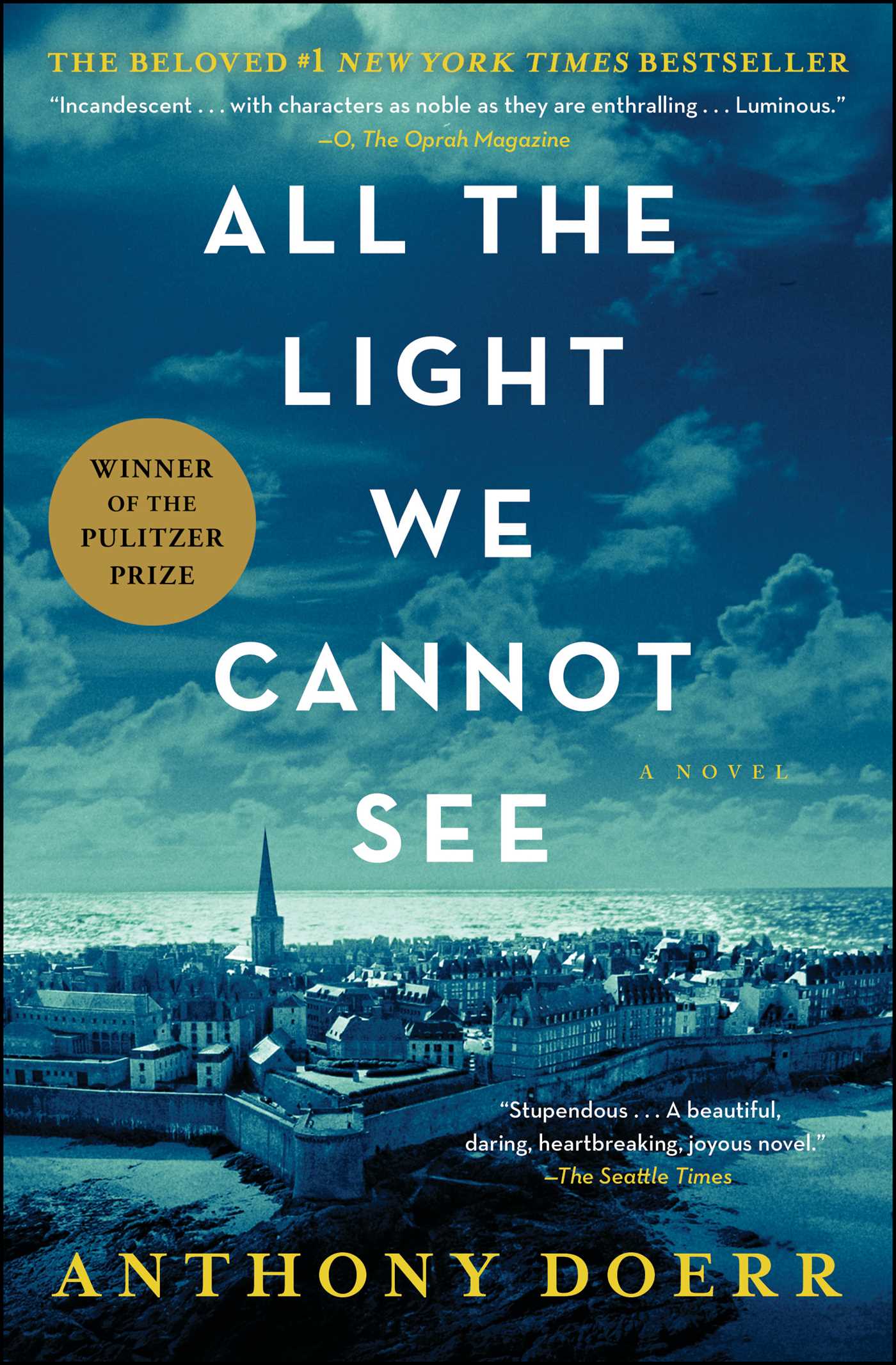

That visit was an early step in a decade-long journey toward assembling the novel that is All the Light We Cannot See. Along the way it became a book about radio: How did the Reich use radio to hammer a warped nationalism into the minds of Germany’s poor? And how did brave souls use radio to resist German occupation, not just in Vichy France but throughout Europe? I also wanted to conjure a time when it was a miracle to hear the voice of a distant stranger in our homes, in our ears.

Ultimately, the novel became a project of humanism. I longed to tell a war story that felt new, and to do that I needed the reader to invest as completely in Werner (the German orphan boy) as she does in Marie-Laure (the blind French heroine). In the war stories I read growing up, French resistance heroes were dashing, sinewy types who constructed machine guns from paper clips. And German soldiers were evil blond torturers, marching in coal scuttle helmets alongside barbed wire. I wondered if things might have been more nuanced than that. Could I tell a story about how a promising boy got sucked into the Hitler Youth and made bad decisions that led to terrible, unforgivable consequences, yet still render him an empathetic character? And could I braid his story with the narrative of a disabled girl who in so many ways was more capable than the adults around her? My attempt in this novel is to suggest the humanity of both Werner and Marie-Laure, to propose more complicated portraits of heroes and villains; to hint at, as World War II fades from the memories of its last survivors and becomes history, all the light we cannot see.