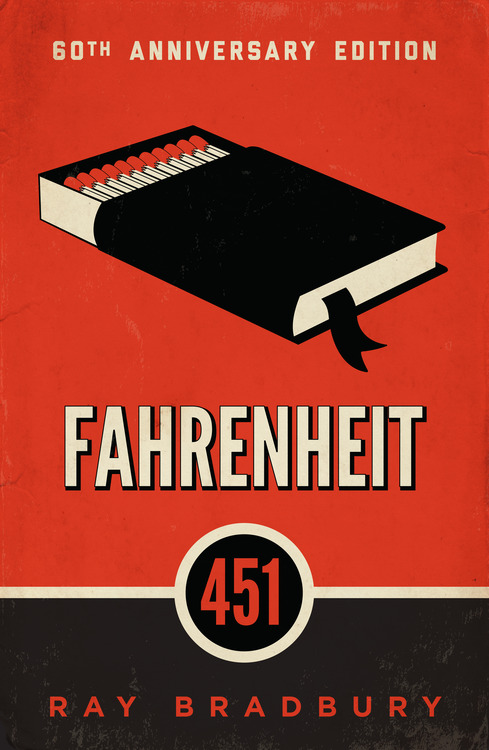

In a recent interview, Donald Glover (aka Childish Gambino) states, “We live in a time when it’s not okay to say the truth and then learn you were wrong later.” As the Internet and its cornucopia of readily accessible information grows more entrenched in our daily lives, it’s hard to imagine how people found out where to eat, reach a destination, or hypnotize chickens without Google. There’s a creeping fear of having the wrong information, holding the “wrong” beliefs, or just not being in the know. After all, how can you not get the joke in this ad, understand the deal with , or have an opinion about Ebola and immigration when decisive opinions already exist all over the Internet for you? In Fahrenheit 451, Bradbury imagines an opposite world, one in which information is severely limited, books are anathema, and Montag, the protagonist, is a fireman who starts fires instead of putting them out. What’s interesting about this novel is that despite imagining a radically different scenario in terms of how much information people can access, the dystopian world of Fahrenheit 451 is only slightly removed from ours.

In Fahrenheit 451, firemen are tasked with dousing books in gasoline and setting them ablaze because books support ideas (and worlds) that are inconsistent, incomplete, conflicting, and chaotic. In their stead, filtered, consistent, and reassuring information is fed to inhabitants to inspire a peaceful world where no one is offended and violence is (theoretically) contained because there are no conflicting ideas to be offended about. Knowledge is essentially being erased to encourage satisfaction and comfort and make sure that everyone is right every time. Yet throughout the book are echoes of restlessness: People jump in cars and drive at high speeds going nowhere in a bid to quell their mysterious anxieties, teens muck about in gangs attacking people to let off steam. Everyone might believe the same things and make the same choices, but no one is truly happy and absolutely no one feels truly alive.

This constant sense of restlessness hovers above our world in a similar manner, despite having access to an overwhelming amount of information. It’s no longer okay to be wrong in public or to just not care about a popular issue, and it’s become harder to embrace the gray areas of belief and the self-awareness they inspire because it’s easy to find out what society believes and go along with it. Reblogging everything on Ebola, placing #feminist on your Instagram feed because Beyoncé, paying extra for foods with organic, non-GMO stickers, laughing at cat memes with your coworkers without really knowing or caring about what you’re saying is fine as long as it sounds right or is generally acceptable.

Gandhi once said (or maybe he didn’t, I could be wrong) something to the effect of “I won’t always be right, but my aim is to tell the truth as it presents itself to me at a given time.” And that’s what separates our chaotic, disordered world from the terrifying sterility of Fahrenheit 451: our individual views, though discordant, inconsistent, or illogical. When we start to whittle our opinions to match the few accepted or encouraged by the majority (and when we refuse to admit that we don’t understand Rainbow cat), we slowly become one of Bradbury’s restless, shadowy humans, unable to decide what’s real and what isn’t among the gasoline-fueled fumes in Fahrenheit 451.