Chris Arnade has a series of photographs showcasing Hunts Point, a Bronx neighborhood which houses—amongst families living in projects, non-profit workers, and junk dealers—drug addicts living between makeshift cardboard homes, in shelters, under train tracks and on park benches, some newly out of jail with an itch that will likely land them back in shortly. To most people, drug addicts inhabit a dark and alien space, as physically removed as possible from mainstream society, with a chronic inability to ever achieve a tax-paying, 9-to-5-job-working, family-having sort of normality. What makes Cocaine’s Son interesting is that the ‘addict’ in this memoir (Itzkoff’s father) is a person who most readers would earmark as normal (in fact, better off in some ways than ‘normal’ people).

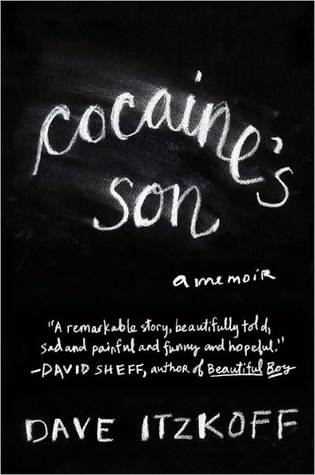

Cocaine’s Son is a tender memoir about the author’s coming of age in the shadow of his father, a fur coat trader addicted to cocaine. Amidst the recent popularization of addiction memoirs that do as much to glorify the pleasurable excesses of drug and alcohol addictions as they chronicle the devastating lows, Cocaine’s Son adopts a less dramatic and perhaps more realistic approach.

Itzkoff’s father’s addiction never quite occupies the platform it’s granted. Instead of conforming to polarizing (and stereotypical) views of drug addicts as ‘others’ different from normal people, he emerges as a father who works hard and manages to keep his family in an upper Manhattan apartment, pays for their education, (and his son’s nose job), and provides as ‘normal’ people are expected to. While the reader suspects that every time he disappears from the narrative he’s somewhere else with his vices laid out, this becomes secondary to who he is when present, and how he attempts to reconstruct the relationships his addictions have unraveled.

Cocaine’s Son isn’t so much about addiction as it is about a father and son trying to understand each other. That one is an addict is a fact that hovers around the periphery of the narrative. Sometimes it’s critical, many times it’s a lot less important than Itzkoff and his father trying to work out the kinks in their relationship. Like Arnade’s photographs, it goes beyond the spectacle of addiction to reach the people behind addictions, the relationships they build and their struggles to become better people.