There is a video online of Leanne Shapton talking about the structure of her book Swimming Studies, which is not exactly a memoir, not a collection of illustrations like her previous books (though there are illustrations in it), and not really a linear, chronological story, either. What she tried to do, she explains, is make the structure feel like water: like when you break the surface of water and the image below fractures into many images—some telescoped, others magnified—to kaleidoscopic effect. What lies beneath is solid and real, and it once looked totally clear—before you reached into the water and tried to grasp it.

This is also the way Shapton describes her feelings about competitive swimming, which is, on the surface, what her book is about. Before she created a string of lovely illustration and watercolor books (Was She Pretty?, Sunday Night Movies) and before she was the art director of the New York Times op-ed page, Shapton spent years competing against the best swimmers in Canada, going as far as the Olympic trials in 1988 and 1992. From the age of twelve she committed herself to hours of frigid, predawn training, to overnight bus trips and damp locker rooms, to discipline and drills, candy-colored towels, technical swimsuits, power bars, false starts and coaches who “stand above you, over you.” Shapton describes these moments with gorgeous precision, distilling her swimming life into a series of refined images that appear to multiply and refract before forming a cumulative, thoughtful reflection of a past life.

But the thing that Shapton is trying to grasp here—the thing that remains as elusive as water—is what it means to no longer be doing what had once defined her. As she considers who she is and who she used to be, we catch glimpses of her life in and around swimming: her suburban childhood; her crowded, record-strewn college apartment; her adult life as an artist in New York; and the hotel pools at the exotic locales she travels to with her husband, James (who is the former editorial director of Condé Nast, I discovered after some obsessive post-reading research). With the discipline of someone used to counting strokes and timing laps, Shapton diligently, eloquently sifts through past and present to dwell on swimming, art, and ambition, and the way in which each informs and defines the other.

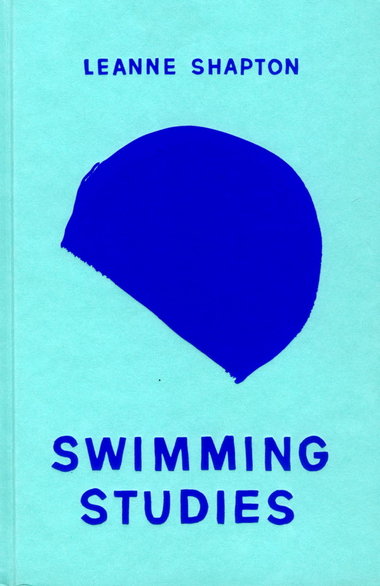

A vivid aqua embossed with a cobalt blue swimming cap, the book is a piece of art in itself. Inside, there’s a photo insert of different types of swimsuits, murky portraits of teammates, and a section titled Fourteen Odors, in which watercolor blobs are paired with poetic descriptions like “10. Coach: Fresh laundry, windbreaker nylon, Mennen Speed Stick, Magic Marker, and bologna.” The influence of swimming on her artwork is obvious.

“Artistic discipline and athletic discipline are kissing cousins,” she writes, “they require the same thing, an unspecial practice: tedious and pitch-black invisible, private as guts, but always sacred.”