When Steve Toltz finished studying video production at university in Australia, he was appalled to realize he’d completed his degree without reading a book. “I thought I’d squandered my education, I got into a panic about it,” he told The Guardian in 2008. “So I went to the University of New South Wales, went to the Russian literature department, said ‘give me a reading list’, and started working my way through it.”

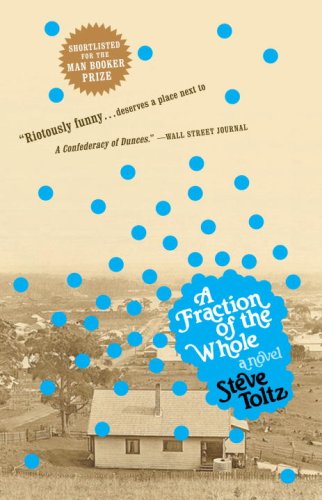

The experience must have been something like a detonation. I don’t know if Toltz intended all that reading to inspire a book of his own, but his 600-page debut, A Fraction of the Whole, became a finalist for the Booker Prize and remains hands-down one of my favorite novels–one I would buy for almost every serious reader I know if I could. It’s the acidly funny story of three men’s misadventures (and I normally hate the word misadventures, but it applies in spades here) from Australia to Paris to Thailand: the demise of hapless, homegrown philosopher Martin; his brother Terry, the infamous criminal mastermind; and his teenage son Jasper, who narrates most of the novel with the cynicism and wonder of someone who’s thrust into adulthood a little too quickly. (Astrid, his mother, remains mysteriously absent.)

Toltz’s plot moves like the end of a live wire, propelled by wild circumstance and incident. Esquire’s review corroborates twists like a massive fire caused by a beam of sunlight through an observatory telescope, or an exploding barge on the Seine: “It reads like Mark Twain with access to an intercontinental Airbus. . . . kite-strung with mind fucks.” But there isn’t a page without the fireworks of Toltz’s prose, and the disastrous results of his characters’ good intentions are as hilarious as they are heartbreaking. And that’s where you start giving A Fraction of the Whole real kudos, because it’s fiction that grapples with the complexity of modern life in a way that actually feels original. Its metaphysical questions about consciousness, mortality, and belief give it a heft that easily equals A Confederacy of Dunces or The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. At the end, when Jasper’s awakened consciousness finally gives him closure about how to reconcile his place in the world, the novel becomes moving in a way that’s as deeply satisfying as the wild ride that delivers him.