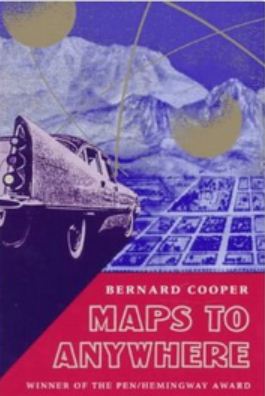

My copy of Maps to Anywhere, Bernard Cooper’s collection of personal essays—perhaps better described, as it is in the foreword, as “a cluster of texts”—is incomplete. Close to the beginning page twenty-four turns abruptly to page twenty-seven: torn paper tucked into the spine is all that remains of the short essay there, entitled “Rain Rambling Through Japan.” After reading it literally hundreds of times, always struck by Cooper’s elaborate metaphor for language, his lyrical prose, and his irresistible (and unfounded) assertion that the Japanese hear the sounds of nature with the part of the brain that processes language, I was compelled to rip it out and mail it to a friend. This part I still remember: “rain is words, important words rambling through Japan, tangents rapidly running down gutters, adverbs darkening the asphalt, adjectives beading the leaves.”

Sitting down to write this review, I regretted not having the full text to work from. But maybe my incomplete copy and the phantom pages I’d partially committed to memory fit with Cooper’s assortment of memories and meditations, with the collection’s lack of a narrative thread and themes of loss and longing. Billed as autobiographical in the marketing copy, Cooper’s essays vary from longer stories of his childhood to short, dream-like anecdotes—almost prose poems—with characters seemingly conjured by his imagination. His fragments of prose make no effort at cohesion or completion, and they question the importance of the distinction between fact and fiction.

“Rain Rambling Through Japan,” for example, begins with a dialogue between a Ms. Thompson and her students, and goes on to tell, using lavish wordplay, of Ms. Thompson’s dream, with no mention of Cooper. It’s difficult to tell whether the pensive teacher is awake or dreaming. In another essay, “The House of the Future,” Cooper tells of his brother Gary’s death from leukemia. Gary and Cooper’s father, an extravagant lawyer with a penchant for odd cases, frequently reoccur throughout the collection.

In another one of my favorites, “Capiche?,” Cooper begins by recounting an Italian lesson about animal noises. Suddenly, we’re in a café in Venice, with Cooper spinning a romantic tale complete with a lithe and handsome stranger who speaks no English. By the end he’s admitted that he’s never learned Italian or been to Venice, that everything he’s just told was a lie. “But lies are filled with modulations of untranslatable truth,” writes Cooper. “All I had was the glass of language to blow into a souvenir.”