When I bring up Shirley Jackson in conversation, people often don’t recognize her name and say they’ve never read her work. To this, I always respond: yes, you have. When they continue to insist they haven’t, I begin to summarize a story: there is an idyllic little town where every year, in order to bring about a prosperous harvest, the villagers choose a town member randomly through a lottery and collectively stone him or her to death. At this point, I usually see a spark of recognition in my companions’ eyes—“Oh, wait, that sounds familiar. I think I have read that . . .”

Shirley Jackson’s short story “The Lottery” is widely anthologized and taught in many high schools and universities. It seems that, while the author’s name and the piece generally fade over time, the story’s haunting scenario stays with people.

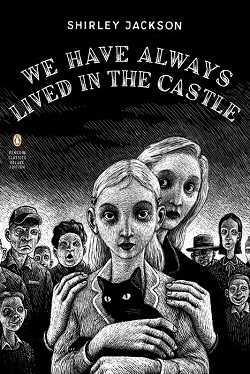

“The Lottery” isn’t Jackson’s only piece of work with this kind of disquieting permanence. I have read her short novel We Have Always Lived in the Castle several times; even when it has been years since I have revisited it and the names of the characters and exact plot details have faded, this story of two lonely young girls ousted from society, their crumbling manor, and their devastating secret remains.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle begins, “My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance. . . . I dislike washing myself, and dogs, and noise. I like my sister Constance, and Richard Plantagenet, and Amanita phalloides, the death-cup mushroom. Everyone else in my family is dead.” Who could forget an intro like that?

The novel proceeds to tell of Constance and Mary Katherine, who live with their invalid Uncle Julian in their manor house on a hill. They are hated by the villagers who live in the town —when Mary Katherine makes a run to the store for supplies, she is bullied and jeered and taunted with the song, “Merricat, said Connie, would you like a cup of tea? / Oh, no, said Merricat, you’ll poison me.” The girls are ostracized and hated because, years ago, almost the entire Blackwood family perished one night over dinner. The cause of death was determined to be poisoning and Constance was widely condemned as the killer. But without adequate evidence to prosecute her, she was released and sent home to what remained of her family: her little sister Mary Katherine and her Uncle Julian, who barely survived the deadly meal and was permanently damaged because of it.

Mary Katherine’s first-person narration is innocent and naive—without knowing, one might guess she was a girl of eight or ten, not eighteen. She loves her sister and her home and their insular life together; she lives in her imagination and regards her cat as almost human. But all is not as it seems in the manor—Mary Katherine is not nearly as innocent as she appears, and her fierce loyalty to Constance is born out of a heavy, terrible secret that the girls share. As their “castle” crumbles around them and the weight of all that is unsaid between them threatens to crush the girls, the townspeople get restless. Their collective hatred and anger towards the rich girl on the hill who got away with murder reaches a boiling point. The girls can’t stay hidden in their castle forever—nor can they hide from the truth.

Shirley Jackson has a keen insight into the darker side of human nature. Her stories delve into the depths of society and individuals in ways that are illuminating and disturbing. After the publication of “The Lottery,” Jackson received hate mail and death threats for years. What about that story angered people so much? I would say, it’s the same thing that is so haunting about We Have Always Lived in the Castle: people read these stories and see themselves in them, see their neighbors, see their friends—and they don’t like what they see. What makes Jackson’s work brilliant is this insight—these stories are chilling on the surface, but have endless layers of implications and discoveries underneath. I learn something every time I read this novel. It is one that for me has lasting resonance.